The University of Richmond will no longer see race or ethnicity in its admission process after the United States Supreme Court ruled to strike down affirmative action.

On June 29, the Supreme Court found the use of race and ethnic preferences in the admissions processes unconstitutional. This ruling against two universities – the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Harvard University – forced other colleges and universities to reevaluate their admissions process.

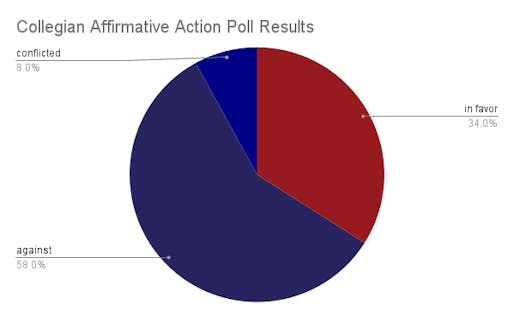

The Collegian used a poll on Instagram to gauge how the UR community felt regarding the decision. Of 26 respondents, 58% were against the ruling, 34% were in favor and 8% were conflicted.

Pie chart of poll results from The Collegian's affirmative action Instagram poll.

At UR, the SCOTUS decision does not change the school’s commitment to diversity, UR President Kevin Hallock wrote in an email to the community.

However, the decision will affect UR’s admission review process, according to an email Vice President for Enrollment Management Stephanie Dupaul sent to the Collegian.

“We will comply with the law and will not be able to see race or ethnicity during the application review process,” Dupaul wrote. “But the ruling does allow us to continue to consider each applicant’s lived experiences as part of their application.”

UR's lack of affirmative action in admissions worries students like junior Ryan Doherty, despite UR’s commitment to diversity.

“This decision will make us finally see if diversity is actually a university value or simply just an obligation to use for publicity,” Doherty wrote in his response to The Collegian’s poll.

Dupaul wrote that diversity is still a part of UR’s admissions process. The Office of Undergraduate Admission holds yearly training on their holistic application review process.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

“We have a very strong applicant pool and admit students from a wide range of cultures, experiences and backgrounds,” Dupaul wrote. “Bringing together this diversity reflects the mission and values of the university and ensures a stronger experience for all students.”

The disparity between the city of Richmond’s demographics and UR’s concerned Doherty, he wrote.

In Fall 2022, UR reported having a 6% Black student population. The city of Richmond’s Black population as of July 1, 2022, is 45.2%.

“Every Black/Brown student that I have met here has the drive and determination to succeed and knows exactly what they want to do to positively impact the world,” Doherty wrote. “It is both disturbing and laughable that these people actually believe they deserve their spot at this university more than the Black students that have always pushed the university forward and kept it accountable.”

Doherty wrote that UR should not use legacy admissions and biased recruiting to benefit white and wealthy applicants.

“If this university is truly as committed to diversity…” Doherty wrote, “and wants its POC students to leave here with ‘spider pride’ and not a mark of shame, there are steps that it can take to curtail this recent decision.”

The admissions office is aware of legacy status when viewing applications, Dupaul wrote.

“We do not award points or use any other formulaic approach in considering legacy status,” Dupaul wrote. “Being a legacy is part of a student’s life experience, just as being a first-generation student is part of their life experience.”

This decision worried other members of the UR community.

“[Affirmative action] simply acknowledges that some students, because of our country’s awful history, have had fewer opportunities to demonstrate their merit and therefore deserve to have their starting line moved up to where everyone else already stands,” Benedict Roemer, ‘21, said.

Affirmative action is a part of not just the college admissions process. The first citing of affirmative action was in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited employers from discriminating against potential employees.

The use of affirmative action in college admissions first came into question in 1978 when Allan Bakke challenged the use of affirmative action in higher education after being rejected twice by the University of California Davis School of Medicine. Bakke said that one of the 16 places reserved for minorities should have been his because his test scores and GPA exceeded that of the minority applicants accepted. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Bakke, stating that the quota violated the Civil Rights Act, but the school was still able to use race as one factor in choosing applicants.

Other UR community members are happy with the decision. Connor Gasgarth, ‘23, wrote comments to The Collegian that colleges should focus instead on income.

“[The SCOTUS decision] is great; race shouldn’t be a factor in decisions,” Gasgarth wrote. “I do think income should be factored into the admissions process, though in a way to replace [affirmative action] so lower-income people still get help.”

Family income is one factor of the admissions process at UR for U.S. residents, Dupaul wrote.

“Being need-blind for our U.S. applicants means we can admit applicants without considering their ability to pay, and we are not limited in who we admit,” Dupaul wrote. “We want students from all backgrounds to attend UR.”

UR also factors socioeconomic status and circumstances into admissions, Dupaul wrote.

“For example, we recognize students from families with less income may be working or caring for siblings, which may limit their participation in clubs and organizations,” Dupaul wrote. “They are contributing to their families and community in equally valued ways.”

Sam O’Rourke, '21, wrote that this decision will benefit students of color.

“Removal of affirmative action opens the door for new policies that actually address the root cause of disparities and put [under-represented minorities] in positions to succeed,” O’Rourke wrote.

O'Rourke agreed with Justice Clarence Thomas’s statements that race and ethnic preferences in admissions make Black and Latino students feel inferior. A study by Angela Onwuachi-Willig, Emily Houh and Mary Campbell showed that racially assigned labels and stereotypes were not different when it came to law students at schools with affirmative action and those at schools without affirmative action.

“The bottom line was that discrimination was occurring, and UNC/Harvard could not give any reason to justify it,” O’Rourke wrote.

The Supreme Court Justices agreed with this sentiment, stating that the elimination of racial discrimination is not on a case-by-case basis. The Supreme Court’s notes stated that the Equal Protection Clause should be universal in application and not exclude college admissions.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote in her statement that the use of the Equal Protection Clause to strike down affirmative action hindered change. The clause was not meant to be used in such a way, she wrote.

“The abolition of affirmative action is a declaration of war against diversity and all the progress that Black and Brown Americans have fought and died for,” Doherty wrote.

Contact executive co-editor Amy Jablonski at amy.jablonski@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now