This Collegian UR podcast explores the memorialization of Robert Ryland and Douglas Southall Freeman at the University of Richmond, gathering different perspectives on their presence on campus today

Hosted, edited and produced by Jackie Llanos. Nina Joss assisted in editing. Music created by Nathan Burns. Podcast art created by Nolan Sykes and The Collegian.

Listen on Spotify | Listen on Podbean

JACKIE LLANOS: The Richmond College Student Government Association and the Westhampton College Government Association joined forces for the first time on April 3, 2019, to call for the University of Richmond to rename Freeman and Ryland Halls, according to a Collegian article published on April 8, 2019.

In May 1965, UR’s board of trustees named Freeman Hall in honor of Douglas Southall Freeman, a journalist who supported the “Lost Cause,” according to an article published by The Collegian on May 21, 1965.

“The Westham Project: A Look at Freeman” will dive deeper into Freeman’s legacy and the “Virginia Way.”

Ryland Hall’s story is more complicated. The building has two namesakes, Rev. Robert Ryland and Charles H. Ryland. The third floor of the western wing, which was the library before Boatwright Memorial Library was built, is dedicated to Charles H. Ryland, a treasurer and librarian of Richmond College, according to a digital exhibit published by Boatwright Memorial Library. The rest of the building is named after Robert Ryland, the founder of Richmond College, according to the digital exhibit. Robert Ryland was also a slaveholder and preacher at the First African Baptist Church. “The Westham Project: Ryland, Religion and Slavery” will further explore Robert Ryland’s history with the church.

At the time of the interviews included in this podcast, the UR community was awaiting the administration’s next steps in terms of renaming Freeman Hall and Ryland Hall. On Feb. 25, 2021, President Ronald Crutcher sent an email to the UR community stating that the name of Ryland Hall would not be changed, but that a new terrace of the Humanities Commons would be named after a person or people who were enslaved by Robert Ryland. President Crutcher’s email also stated that the name of Freeman Hall would be changed to Mitchell-Freeman Hall, in order to recognize John Mitchell Jr., a prominent Black editor of the Richmond Planet. Although a decision has been reached, the perspectives included in this podcast are an important reflection of community members’ thoughts about memorialization.

In this episode, we will be discussing why memorialization matters. We will also be highlighting students’ push for change in whose story gets told and how.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

I'm Jackie Llanos, news editor for The Collegian, and this is the Westham Project on Beneath the Surface, a Collegian podcast.

[music plays]

Before we dive in, it is important that we take a moment to acknowledge our inherent shortcomings in the creation of this podcast.

The Collegian is a predominantly white institution on campus, and we are aware that this lack of ethnic and racial diversity on our staff, specifically regarding our staff’s lack of Black representation, will have an effect on how we report this story.

As The Collegian strives to serve its stated mission of reporting the truth accurately and inclusively, we believe it is important to be transparent in this shortcoming and reemphasize our dedication to improving our organization in all areas of diversity, equity and inclusion.

The student government resolution to change the names of Freeman and Ryland Halls came after the Princeton Review’s Ranking of UR as 9th in the “Little Race/Class Interaction” category, RCSGA President Anthony Polcari said. UR currently ranks as 10th in that category, according to an article published by The Collegian on Sept. 21, 2020.

Tyler York, the president of RCSGA in 2019, asked Polcari to write the resolution, Polcari said.

York did not respond to The Collegian’s request for comment.

ANTHONY POLCARI: He and I were talking about it, and he said, you know, “I'm thinking about -- maybe the student governments should sponsor a resolution to change the names.” Because remember at the same time, Georgetown had just done something very similar.

LLANOS: Polcari is referring to Georgetown University’s dedication in 2017 of one of its buildings to Isaac Hawkins, who was one of the 272 people enslaved at Georgetown, according to an article published by the Georgetown administration on April 13, 2017.

Later in the episode, we will talk about how George Washington University, Robert Ryland’s alma mater, then known as Columbia College, has handled students’ calls to change its moniker, the “Colonials,” and other building names.

Although the administrations of universities such as Georgetown and GW had already taken strides to change who is memorialized on their campuses, UR’s student body was in the middle of debating whether to call for the administration to change the names of Freeman and Ryland Halls, Polcari said.

POLCARI: The fact that we’re in the capital of the Confederacy and we haven't, you know, we're right in the middle of it, and we haven't addressed that -- even before we knew about the burial ground...the fact that we weren't addressing this? And in the, in the aftermath of Charlottesville -- this is the two years, almost two years after Charlottesville. So, I felt the university was kind of asleep at the switch.

LLANOS: For Polcari, the perfect solution would be to take Freeman and Ryland’s names off the buildings, but he would be open to having a plaque contextualizing the removal of the names, he said. He also favors changing how UR names its buildings and would like to see buildings named after astronaut and UR class of 1986 graduate Leland Melvin or UR’s first Black student Barry Green.

POLCARI: I just can't in good faith, you know, force a student to walk into a building that had been named after someone that didn't view them as fully human. I mean when you, when you break it down -- when you break it down to its, to its -- in its simplest form, that's what this man believed, no matter what he did for the university.

[music plays]

LLANOS: Dominique Harrington graduated from UR in 2019 with a Bachelor’s degree in American Studies. She was a fellow of the Race and Racism Project in the summer of 2017, where she learned about how UR portrayed its history. She was also an Oliver Hill scholar and a co-founder of Shades of Pride, an affinity group for queer students of color.

Like Polcari, Harrington favors Freeman and Ryland’s names being removed from the buildings, she said. She also sees contextualization of the name removals as an option, she said.

DOMINIQUE HARRINGTON: Institutions kind of show what they value in how they name things and how their infrastructures are set up. So, I think that I, personally, would like to see the name changed. And I think that even if the name was changed, I think that there could be a place in the building where there should be, like, an exhibit or something like that showing that this was Ryland Hall, and this is why it isn't.

And just because we valued, I guess, this man at one point in time doesn't mean that we have to stay the same forever really.

LLANOS: As an American Studies major, many of Harrington’s classes were held in Ryland Hall. She also took some of her graduation pictures in the building, she said. Ryland’s background as a holder of enslaved people did not cross her mind often because being in spaces that have ties to the oppression of Black people is the norm, she said.

HARRINGTON: As, you know, a Black person on the -- on campus, as a Black person in this country, it's kind of the norm that the spaces that I'm in weren't built with me in mind in the first place.

So I kind of assumed that, like, you know, “This probably has some ties to something, you know, shady regarding racism, slavery.” Jim Crow, whatever -- it’s kind of an assumption that if this institution has been here longer than, you know -- whenever, you know -- it doesn’t even have to be a time frame.

But if this institution, you know, University of Richmond has been here since, you know, ties to it since the 19th century -- I'm going to assume something racist, something connected to slavery, Jim Crow or whatever has happened. Because that's just the way that things work in this country.

LLANOS: Despite the memorialization of those who contributed to the oppression of Black people being the norm, Harrington sees ample ways for improvement on top of renaming the buildings, such as educating students about the history of UR during orientation, she said.

HARRINGTON: I think that could be an opportunity to kind of prime students on, "This is the space that you're entering; this is the history of that space." And, kind of, the weight that that holds and how we navigate it today.

So, I think that the conversations have started. I'm not sure what those conversations look like now since it's been a minute since I've been back to campus. But I think that there's always more work to be done.

LLANOS: In regard to naming buildings after people, Harrington doesn’t have a problem with doing so, but she is critical of the unwillingness to rename those spaces as the values of institutions change.

HARRINGTON: I think the problem lies in not wanting to change as we change as a people. For example, I think that, you know, if Ryland Hall were to be named after Barry Green, I think that that could be incredibly powerful -- the first Black male student in the residential facilities to graduate from the university.

I think that that could be, you know, incredibly powerful, not only for the university to kind of say, not only in words but in deeds, that, ‘This is what we value as an institution, the Black students that kind of paved the way for the university and for other Black students.’

So I don't, I don't think that there's a problem inherently with naming buildings after people. I think that the problem lies, number one, with not wanting to change, or not being open to change; and number two, the role that money plays in naming buildings after people.

Because, you know, people give money to the university and then, you know, their name goes on the building. But that money doesn't inherently mean that they embody the values that the university wants to continue to embody from that point moving forward.

LLANOS: Harrington noted the time it takes for universities to catch up to the evolving values that might require for the university to make a change in its operations.

HARRINGTON: Institutions, as they tend to exist, especially institutions of higher education, are slow, just in general. They're very slow to, you know, change and move forward, and that has a lot of reasons -- a lot of reasons I understand. But at the same time, it's still slow.

I feel like typically the way institutions work is, like, “Okay, we're going to found a commission to study the possibility of, you know, memorializing or whatever.” And then that commission will give recommendations, and then there will be another commission to look at those recommendations and see how they will be implemented. And then there's another commission to kind of talk to the board to see how the board would feel about changing whatever.

And it's just, it's a lot. It really is.

LLANOS: Circling back to the Princeton Review’s ranking of UR as 9th in the “Little Race/Class Interaction” category in 2019, Harrington sees that as an indication of a bigger issue that would not be solved just by renaming buildings, she said.

HARRINGTON: It can't just be about symbols. So I think I’m -- I think that names matter. I think that memorialization matters. I think that it's, it's impossible to go through an American studies degree, you know, without thinking that memorialization and memory matters.

Let me be clear in saying that I don't think that this is the most important issue that the university has to solve. I mean, we're what? When I was there, we were number nine regarding segregated universities in the country.

So I think that it kind of comes in tandem with the university acknowledging its past and also figuring out a way to support the marginalized, specifically the people that the university has marginalized in the past. So supporting the marginalized, acknowledging the marginalization that has happened and moving forward. And I think that all of those things kind of happen at once.

I just think that if we're going to change the names, we have to also, kind of, you know, put our money where our mouth is. Change the names, but also support these initiatives like the Race and Racism Project, and support Black students, you know, and institutional un-learning and re-learning kind of across the board.

[music plays]

LLANOS: With the idea of supporting students of color, Chaz Barracks, a scholar-in-residence at the Bonner Center for Civic Engagement and instructor of the Rhetoric and Communications Department, decided to come back to UR.

Barracks attended UR from 2007 to 2011 as an undergraduate student majoring in criminal justice, a program that no longer exists at UR.

He came back to UR from 2014 to 2016 for a master’s degree in nonprofit studies. Barracks became an instructor and scholar-in-residence after earning a PhD from Virginia Commonwealth University in philosophy and media, art and text.

Having been a student and a faculty member at UR, Barracks has witnessed how long it takes for change to happen, he said.

CHAZ BARRACKS: There was definitely a lot of, as I said, like, discussion about diversity and inclusion on campus. And I think that as a part of, you know -- as an honorary member of the Black students alumni at UR, I do think that a lot of us were, were talking about, you know, just finding our own sense of belonging on campus.

And not always feeling like we had to be a part of this, like, multiculturalism, diversity and inclusion kind of initiative? But just like, you know, being treated right on campus, having the same access to resources that other student groups had.

So really, as I, as I said earlier, like -- just tying this kind of, taking this diversity inclusion thing away from it just being theory, and really thinking about it as, like, practice.

And I think a lot of friends that I had at University of Richmond still talk about these things today.

LLANOS: For Barracks, the end goal is seeing students of color enjoy their college experience, he said.

BARRACKS: A part of me thinks that the university has changed a lot. Like aesthetically and physical things have changed, like buildings, et cetera. But then it also feels disheartening that students are, kind of, still fighting for the same thing. And it just like, maybe looks a little different.

But I do think that a shared connection between what I see Black students at University of RIchmond fighting for now, like, establishing an Africana studies major, which like -- like, why not, you know? The fact that students are fighting for those types of things that, you know, administrators should have changed a long time ago, or administrators should be, you know, aware that these changes need to happen now, not before the 2020 you know, quote unquote, pandemic

Because for, for me as a Black person, like this is my second pandemic. Racism has been a pandemic since before I was at U of R and now in 2021.

So, it is disheartening in a way because it's like I -- as a professor or faculty at University of Richmond -- just as a member of the, even of the alumni community, I want to see a day where Black students and POC students and other students who are labeled as marginalized can just have the college experience, right? Can, can fight the fight if they want to, but then also can have the choice to, to be a college student. To just be. To have fun, to party for too long and struggle to get to class next morning, like to have all those experiences that they deserve, right?

And I always wonder, when I read all these things about student groups fighting to change building names, fighting to have a major that recognizes their identity as well -- I always think about kind of the invisible labor that goes into those fights.

LLANOS: Barracks believes that the push from the student body to change the names of Freeman and Ryland Halls should be enough for the name change to occur, he said.

BARRACKS: When we talk about why this matters, in terms of changing names of academic buildings that are named after slave owners in, in, in a very troubled, in complicated histories, right? You can't just look away at their troubling history in order to say like, ‘But there, there was good.’

Because I think that specificity matters, and that we have to think about, like: what message are we still sending as an institution in this moment, especially, having buildings named after someone like Ryland. And I think that we're in a moment in what will be our history. And I don't think it's enough to just honor those names. And, you know, look away at the way that it still brings up a traumatizing history to certain populations of students who do matter -- right, our voices do matter.

And if I'm, you know, tasked to making University of Richmond a better space, as a Black alumni, as a Black professor, as a Black community member that is involved in the university -- then I don't think I should have to walk by buildings that bring up a traumatizing history.

LLANOS: When it comes to the question of how institutions should name buildings, Barracks believes they should not be named after any person, he said.

BARRACKS: I want to answer this question with just saying I hope that the university does the thing that makes Black students and POC students feel heard and feel and feel valued in this moment in this moment, in this cultural moment.

And I think my second answer is like, personally, like, as Chaz Barracks, like -- I am just not really interested in, like, this concept of naming in general. Even if I had $3 million and decided to give my alma mater $1 million, like -- I would give it from a place of care, and a place of love that, you know, I tie to all of the things that I commit to in my career.

So for me, I just think that everyone has a complicated past. But of course, some people have, you know, traumatizing and heavily complicated pasts, but we're all humans, and we're, and none of us are perfect. And I just think that, like, why do we keep having this kind of obsession with naming buildings that everyone has to use after one individual?

Kind of, like memorializing of individuals -- it just doesn't really sit right with my spirit, it's not something that I'm interested in. I think that if we moved away from that, we would see who still gives money and who doesn't. And then that would give us a way to act, to, to assess like, are folks giving money for, you know, care and loving reasons? Or are they giving it for this type of like, you know, false representation that they are this almighty, perfect person, right?

So I just, you know, I ask, you know, “What purpose does it serve in a space, like a university campus to continue to have that, that tradition of naming things after one individual?”

LLANOS: UR is not exempt from the tradition of naming buildings after donors, such as the newly-opened Queally Athletics Center, named after Paul and Anne-Marie Queally who donated $7.5 million toward the building, according to an article published by the Richmond Times Dispatch on Oct. 16, 2020.

However, it is worth noting that neither Freeman nor Ryland Halls were named because the men donated money for the construction of the buildings, but because UR wanted to honor their contributions to the institution.

Contrary to Barracks, Julian Hayter, professor of leadership studies, doesn’t think the reminder of systems of oppression is a compelling enough argument to rename a building, he said.

JULIAN HAYTER: What y’all need to be asking people who are asking for the removal of names from buildings is, “What do you plan to do to preserve the memory of these caustic ideas so that we can finally come to terms with them?”

Because if -- if the objective is to make these names go away, simply to make people who are on campus now feel good about themselves, then that's the -- that’s the wrong damn approach. Right?

Especially in an institution of higher learning that's invested in education. Right? I mean, we have an obligation, right, to keep the memory of these ideas alive, even if they're disturbing.

Disappearance is what I'm afraid of, right, simply because, you know, people lack the kind of sensibilities to deal with the darker chapters of our, you know, of our tortured history.

LLANOS: If the buildings were to be renamed, Hayter proposes using it as a teaching opportunity, so future generations will learn why the names were changed.

HAYTER: But I think if if it's done away with, if the decision, I mean if the decision is to remove these names and there isn't a plaque, a history that is visible, that people can see the kind of thought development that led to the removal of that name, why people came to that decision … then it's -- not only is it a squandered opportunity, it's morally irresponsible.

If America had actually come to terms, right, with its racist past, this shit would be a punch line, right? The reason why we're still relitigating this stuff is 'cause we all know that something is wrong, right?

That continuity of these ideas and the continuity of these bad practices, or the continuity of practices that these bad ideas led to, has led us to re-interrogate the past because we haven't gotten over it. So washing it away, in large part, is going to do nothing to come to terms with the institutional implications that still continue to plague this society, that these ideas begat in the first place.

Right? So you've got to come to terms with the historical legacy.

Everybody wants to be the person who was responsible for, you know, bringing this shit to an end. But that's not going to do anything to help us move forward.

LLANOS: Yet, Hayter recognizes that the monuments and building dedications, as they are, do not serve a historical purpose, but rather a celebration of heritage, he said.

HAYTER: I think ultimately, if memorials aren't used to tell a full and accurate history, then they're worthless, right? Then they're about heritage and not history, and heritage is different from history in that people pick and choose the memories chosen. And history is an interrogation between historical method, evidence and scholarly expertise.

And what we've seen is that Confederate iconography isn't interested in the truth. It's interested in Southern heritage, which is not completely devoid of the truth, but it picks and chooses the truths that it wishes to portray.

And any monument that serves in defense of half truths, flat-out lies or falsities, especially in public space, needs to be thoroughly interrogated on those grounds. And I think what we found is that even monuments that stand without context tell a story. And they tell a story in large part because many Confederate monuments and Confederate iconography was erected in the South when there was no popular mandate.

LLANOS: Illustrating the progress society has made cannot be possible if monuments are taken down and names are stripped from buildings, Hayter said.

HAYTER: What future generations need to know is that at one point, America was fucked up. And people challenged how fucked up it was and came to terms with the ideas that led up to it's fucked-up-ness.

And the only way future generations are going to learn how to come to terms with their own problems is see how we worked through ours. You can't make that shit go away.

[music plays]

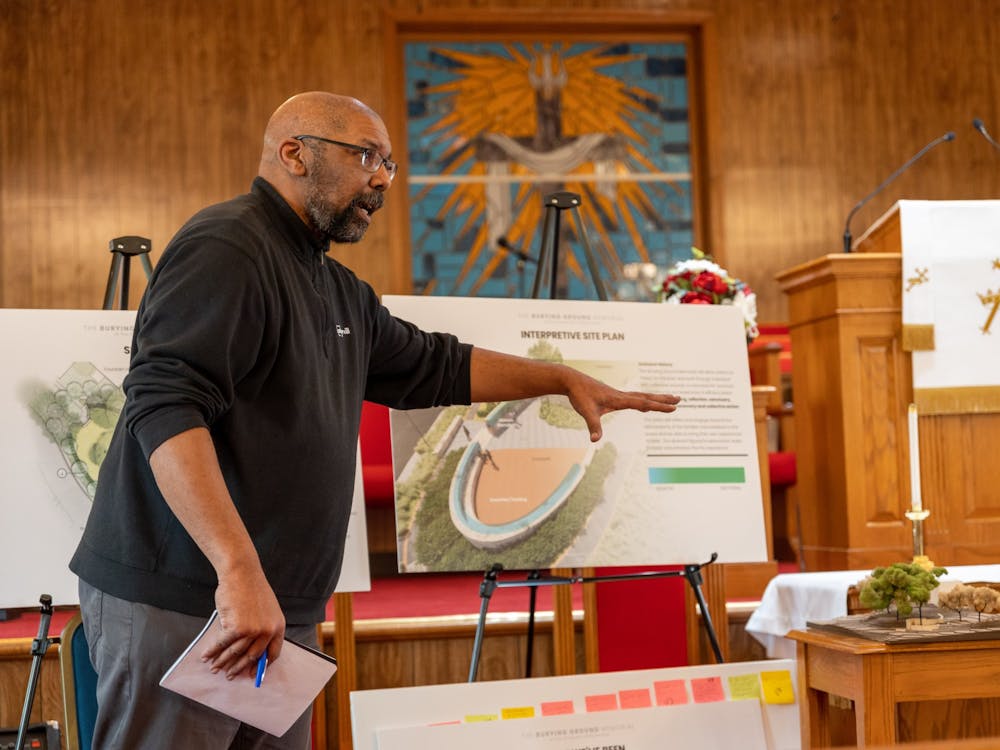

LLANOS: The Presidential Commission for University History and Identity stated that during 2019 and 2020 a report would be made about Ryland, Freeman and the Westham Burial Ground, according to a document outlining the recommendations from the commission.

The document also states that President Ronald Crutcher might form a separate commission to consider making a recommendation to the Board of trustees for the possible renaming of Freeman and Ryland Halls.

Edward Ayers, former president of UR, current professor of American Studies and co-chair of the commission, applauds students for pushing the administration to acknowledge its history, he said.

EDWARD AYERS: When Dr. Crutcher asked me to chair, to co-chair of the commission, we decided it would be useful if people had an evidentiary base for the conversation, right? When the fullest account of Robert Ryland was something that I wrote to give a talk, that's not really enough.

So we needed to know more. And the same thing is true for Freeman.

So I think, you know, the students to note that one man grew up in the world of slavery and another man world in the world of segregation -- it’s, it's appropriate for the university to talk about. And so I think that it’s, uh -- it shows you how things change.

I felt when I was president, you know, that history really wasn't at the top of many people’s, many students’ minds, right? You've got your young lives to beholden.

And it seemed, you know, we had plenty of volunteers who would come to the events that we did for the Civil War stuff and so forth, but -- it just wasn't, you know, something that people seemed to care about very much.

And it's interesting, then, that there's been an awakening, in the country. We suddenly realize that monuments and names have meaning. And so I think that it's a good thing. That the -- and it was great to see the two student government organizations collaborate and do all that. And so I think it is a conversation whose time is coming.

LLANOS: Ayers believes the issue of renaming Freeman and Ryland Halls comes down to what it would accomplish, he said.

AYERS: What’s the meaning, both of Robert Ryland and of Douglas Southall Freeman, and of the meaning of their names on the buildings? And of the meaning of what it means to live with that legacy today?

Does it give us an obligation to not merely acknowledge that, but to do something ourselves? You know, it's not as if the issues of racial inequality have been solved. It's not as if issues of injustice have gone away.

LLANOS: To truly understand a person, one must understand the reasoning behind their actions and the world they lived in, Ayers said. He hopes the UR community is ready to discuss the nuance behind the stories of Freeman and Ryland, he said.

AYERS: People are going to wonder in the future, ‘How did they live with people begging on street corners? How did they allow that amount of homelessness in 2021? How did they, you know, how did they allow people mentally ill not to get the, the, the care they deserved?’

So it's not -- we're living with these blindnesses and silences ourselves, too. And so people wonder how, “How could they tolerate that?” Well, people are going to ask how we tolerate the injustices that we tolerate.

So -- that’s why I think that understanding the world of Robert Ryland helps us understand the world of ourselves. Because we're not that far removed in time, certainly not in place.

LLANOS: To hear Ayers’s more in depth perspective on Freeman and Ryland’s legacy, you can listen to “The Westham Project: A Look at Freeman” and “The Westham Project: Ryland, Religion and Slavery.”

[music plays]

LLANOS: In June 2020, GW released its renaming framework, which was created by its Board of Trustees’ Naming Task Force. André Gonzales, a 2020 graduate of GW, was one of the students on the task force.

Gonzales became interested in the student government’s initiative to change the moniker of GW, the “Colonials” because of his Comanche background, he said. He characterized the change from his life in New Mexico surrounded by Native communities to attending a primarily white institution as "eerie."

ANDRE GONZALES: The realities of you know my family's history within New Mexico and of the Native communities and, you know -- those are things that are passed down and those are things that we are, that I was taught to really … take notice of. You know, regardless of where I'm at, right?

And so to go from that mindset -- that, that mindfulness of, you know, the land that you're on, the histories that it carries -- to go from that to then to, in a predominantly white institution whose, you know, pep rally was called “the colonial invasion.” Who, you know, it’s “colonial dining”; it's colon- you know, if you need to go get paperwork done you're going to "colonial central"; if you need, you know, that -- it's just kind of spattered around.

LLANOS: The biggest obstacle for the GW student government was the back and forth with the administration, Gonzales said.

GONZALES: Regardless, a light needs to be shown on how these institutions are making decisions, and how they're, again, either implicitly or explicitly condoning, the further marginalization, the further erasure of communities that have been here.

This is all to say that GW has done certain things correctly. They have made, you know, efforts to go towards land acknowledgments, towards creating relationships with the Piscataway communities of whose ancestral lands, you know, the GW campus occupies. Right?

But there's, you know -- the fact is is that while, while these discussions were going on, while I was a student sitting in these spaces, I was also sitting in dinners with trustees having to explain to them, you know, why it wasn't appropriate to use a certain racial slur to refer to Native Americans.

LLANOS: GW’s student body’s push for renaming began on March 8, 2017, when student leaders held an event to discuss renaming the Cloyd Heck Marvin Center, citing the former president’s support of segregation, according to an article published by the GW Hatchet.

Following numerous discussions regarding the Marvin Center, the “Colonials” moniker and other buildings, 54% of students voted in favor of changing GW’s moniker, according to an article published by the GW Hatchet on April 1, 2019.

The task force Gonzales became a part of was formed in November 2019, according to an article published by the GW Hatchet on November 21, 2019.

It took GW two years to form a task force to create a new structure for how the process of renaming buildings would work.

Gonzales recommends that students who are fighting for systemic changes in their universities keep in mind that the people in charge of the institutions are also human.

GONZALES: As a student of color who is, who is having to go navigate these spaces -- what brought me both comfort and also energy was, was knowing that the very spaces that I was bringing these questions up, and the very people and the very institutions that I was questioning were not designed for people like me to even be in.

And in that comes a great responsibility, but also it comes with a necessity to be mindful of that. I think that, in these movements -- I fell victim to this myself -- that in these movements, you get so convinced that you are on the right side of something, that you are fighting the right fight, that you -- you know, that your story is the right story.

But there are times in those conversations and in those, in those debates, where passions are high and tensions are flaring that, that I've learned that really acknowledging the humanity of the situation, the humanity of, and the humanity of the person that you're dealing with, matters.

And that's just something that I learned from home.

There's something very powerful and that -- I feel like the most work that we really got done within the task force was when we had dinner at the university president's home and you know, had, had drinks and talked about these things, right? And we let our guards down, and we caught -- we saw each other as equals. And we, we were able to have those difficult conversations.

But after that I was able to see my counterparts -- you know, people several decades older than me -- but at least I could see where they were coming from. I could see that they had families. I could see that they had passions that they had -- you know?

So at the end of the day, yeah, when passions, when passions are high and tensions are flaring, acknowledge that. Acknowledge that there's something that can go beyond just that, that fighting and that gridlock. Sometimes, sometimes you, you realize that you don't get the ball as far forward as you can -- but you know it's still, it's still meaningful progress.

LLANOS: As of February 2021, GW has not made a decision on whether it will change its moniker or rename the Marvin Center, but there are two special committees investigating the requests, according to the Name Change Request website. Other name change requests will be processed once a decision has been reached regarding the moniker and the Marvin Center, according to the website.

[music plays]

In awaiting the reports from the Presidential Commission for University History and Identity about Freeman and Ryland, Polcari said he expected the Ryland family reaction to be the biggest obstacle in changing the name of Ryland Hall.

POLCARI: And, you know, how does his family feel about it? And how would that impact the relationship between the family and the university going forward, way beyond my years here?

LLANOS: Robert Ryland’s great, great nephew and Charles H. Ryland’s great grandson, Jamie Ryland, who still donates to UR along with his five siblings, is waiting for UR to release the report to voice his opinion, he said. Jamie Ryland graduated from UR in 1975, according to UR’s 1975 yearbook.

JAMIE RYLAND: I've got confidence that, that this report will be scholarly and, whatever comes out of it -- it'll be kicked around that -- I don't expect this report to be: ‘Hey, we have decided to do such and such. And that's it. No more talk.’

I don't expect it'll be that; I'll be surprised if it is that. I'm expecting it's going to be an in-depth study showing all sides of whatever the issue is. That it's, I don't -- I don't want to call it a controversy because it's just an issue. And time moves on, and we all have lives to live, and we're living in the present and preparing for the future.

LLANOS: He compared the question of renaming Ryland Hall to the removal of Confederate statues on Monument Avenue.

RYLAND: It's like the monuments coming down off of Monument Avenue. I've seen them my entire life, and I'm sad, but I understand it. And they had to come down.

So I think that I have noticed, of course there's an -- there’s an evolution in my thought. And I think there ought to be evolutions in everybody's thought. You can't just have a belief or you can't think a certain way, just because, ‘Hey, that's the way I was taught, that's the way I grew up.’ So that, there has to be some progress.

LLANOS: Jamie Ryland doesn’t know whether he would support the name change, but is open to discussion, he said.

RYLAND: I fully expect there will be opportunities for rebuttal. And could be that I'll be one of them, saying, ‘Oh, I agree with this, and I don't agree with that.’ So, I think everybody has an obligation to do that kind of thing -- and not get upset about things just because they trampled on your family legacy.

LLANOS: Although Polcari can’t put himself in the shoes of the Ryland family, he would like for them to understand students’ desire to rename Ryland Hall, he said.

POLCARI: But I would ask them to consider maybe changing how they would memorialize their [ancestor], and maybe appreciate where students, you know, where Black students are coming from -- and our entire student body in general that supports this -- where we're coming from. And how we want to, you know, really send a message that, you know, we have to get rid of monuments to slavery and to white supremacy.

And we have to recognize that -- even though it's a family member, you know, even though it might be a family member for them, I think I would ask them to recognize that. And maybe, you know, join us in that effort.

LLANOS: Polcari said the administration had been supportive of the student governments' resolution, and that UR had taken great strides to acknowledge the history of Freeman, Ryland and the Westham Burial Ground.

POLCARI: It's been a long time but I think we're -- I think we're gonna get, finally, some type of resolution to this.

[music plays]

It's important to acknowledge that although UR has reached a decision regarding the renaming of Ryland Hall and now Mitchell-Freeman Hall, conversations about memorialization on our campus are far from over. The Collegian will continue to cover community dialogue and discussion about these topics on campus.

Thank you for listening to Beneath the Surface, a Collegian podcast.

This episode was written, narrated and produced by me, Jackie Llanos.

Gedd Constable, Nina Joss and Grace Kiernan contributed to reporting.

The episode was edited by Nina Joss.

And our music, as always, was provided by the amazing Nathan Burns.

We’ll see you next time.

Contact news editor Jackie Llanos at jackie.llanoshernandez@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now