This Collegian UR podcast explores the life of Douglas Southall Freeman and how he perpetuated systemic racism in Richmond and the U.S. by promoting Lost-Cause Ideology.

Hosted, edited and produced by Gedd Constable and Mia Lazar. Nina Joss assisted in editing. Music created by Nathan Burns. Podcast art created by Nolan Sykes and The Collegian.

Listen on Spotify | Listen on Podbean

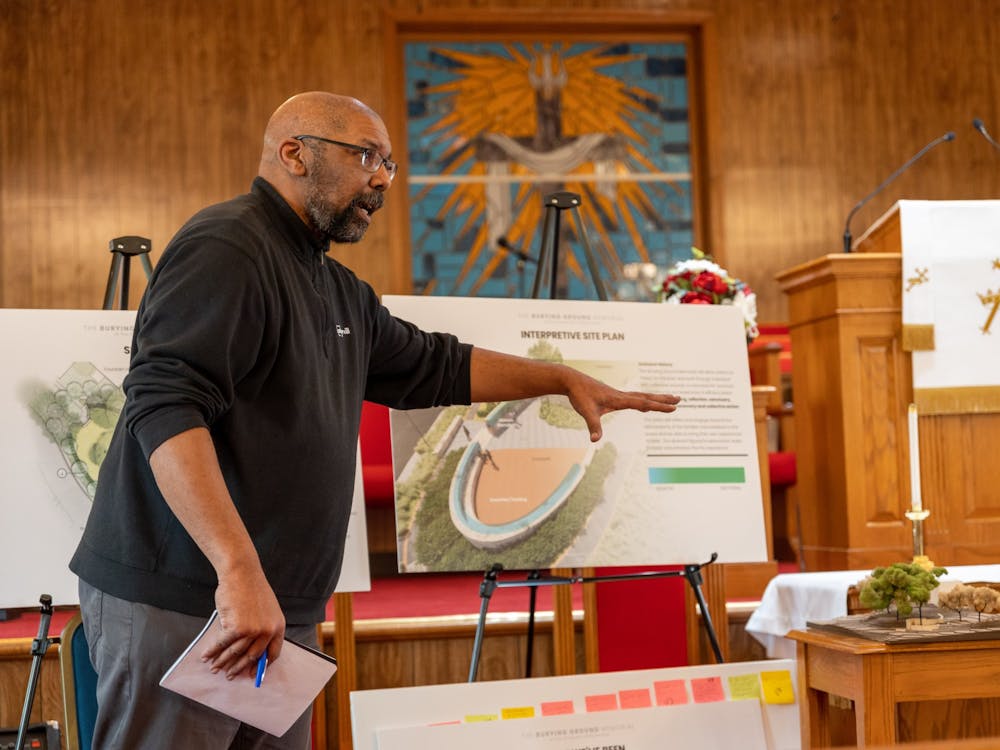

GEDD CONSTABLE: Within the context of national conversations about monuments and memorialization, the University of Richmond is interrogating its relationship to and history of race, racism and memory. In light of the acknowledgement of the Westham Burial Ground by UR in 2019, where enslaved people are buried on campus, memorialization has been at the forefront of these conversations. Outside of investigating the stories of the enslaved people who lived here, our campus community has been grappling with the complexities of the figures we already recognize, specifically those on our buildings.

In our last episode, we examined Robert Ryland, one of the namesakes of Ryland Hall, and his relationship to race and religion in Richmond. If you haven't already listened, check out his story in our last episode, “The Westham Project: Ryland, Religion and Slavery.”

This episode will examine the life and legacy of the namesake of Freeman Hall. One of the three smallest residence halls on UR's campus, Freeman Hall is nestled at the front of the grove of the “Richmond College” buildings on the academic side of campus. Housing 86 upperclass students each year, the building was built and named after Douglas Southall Freeman in 1965 because of his "long and faithful service to the university," according to a 1978 article in The Collegian.

Along with Robert Ryland, Douglas Southall Freeman has been one of several names in the spotlight. In the fall of 2018, UR president Ronald Crutcher charged his Presidential Commission for University History and Identity with investigating University history and its implications for our current campus climate and the future. One of the Commission's recommendations was that a further investigation and report be made about Ryland, Freeman and the Westham Burial Ground, according to a 2019 document outlining the commission's recommendations. The document also states that President Crutcher might form a separate commission to consider making a recommendation to the Board of Trustees for the possible renaming of Freeman and Ryland Halls. On Oct. 30, 2019, President Crutcher released a letter to the community that stated that the research on Ryland and Freeman had commenced.

On Feb. 25, 2021, President Crutcher sent an email to the UR community that included the finished reports about Ryland and Freeman, which provide deeper insight into much of UR’s history, including the complexities of Freeman’s story. In addition, it announced that the name of Freeman Hall would be changed to Mitchell-Freeman Hall, in order to recognize John Mitchell Jr., a prominent Black editor of the Richmond Planet.

As the UR community reflects on this decision, it is undeniable that Freeman's name will continue to be a part of campus conversations. Behind the name lies a complex character and identity.

[music plays]

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

I’m Gedd Constable and this is the Westham Project on Beneath the Surface, a Collegian podcast.

[music plays]

Before we dive in, it is important that we take a moment to acknowledge our inherent shortcomings in the creation of this podcast.

The Collegian is a predominantly white institution on campus, and we are aware that this lack of ethnic and racial diversity on our staff, specifically regarding our staff’s lack of Black representation, will have an effect on how we report this story.

As The Collegian strives to serve its stated mission of reporting the truth accurately and inclusively, we believe it is important to be transparent in this shortcoming and reemphasize our dedication to improving our organization in all areas of diversity, equity and inclusion.

Douglas Southall Freeman was a distinguished UR alumnus, a nationally-known historian and a news editor based out of Richmond. Freeman was a member of the University of Richmond’s Board of Trustees from 1925 to 1950, and he served as the Board’s rector for sixteen of those years. Freeman’s work on the lives of Robert E. Lee and George Washington earned him two Pulitzer Prize wins for biography.

Freeman was also an admirer of the Confederacy. On his way into work each morning, he would salute the statue of Robert E. Lee in downtown Richmond.

Freeman’s connection to the Civil War and the Confederacy traces back to his earliest years. Freeman was born in Lynchburg, Virginia in 1886, and the Confederacy was a central part of the Freeman family identity. His father, Walker Freeman, grew up in a slave-owning family.

Walker joined the Confederate army when he was 17 years old and fought until Appomatox. As a child, Douglas Freeman would dig around Richmond’s battlefields to try to find civil war relics. His daughter once said of her father, “respect for a confederate officer was one of his first strong concepts.”

CONSTABLE: Professor Edward Ayers, a Civil War Historian, the former president of the University of Richmond and co-chair of the commission, believes that Freeman’s family had a significant impact on his work.

EDWARD AYERS: From what I know -- actually, I directed a dissertation on Douglas Southall Freeman that’s now a prizewinning book -- um, and, so I remember that, um -- his father was the big influence on him. That he admired his father so much, and that I believe he spent a lot of his adult career kind of trying to honor his father. I'm sure you've read the story of him saluting the Lee statue on his way into work every day -- things like that.

So the Lee statue goes up in 1890, but the other go up in the first decade of the 20th century, by and large, right? So that means that Douglas Southall Freeman's formative years are the same years that the United Daughters of the Confederacy put up most of these statues and the Sons of Confederate veterans are working to keep the memories of their fathers alive.

That’s because their fathers are dying at that age, right? That’s sort of the story of why they’re doing it. “We want to remember these men before they pass from the scene.”

CONSTABLE: Freeman’s love for the Confederacy was encouraged outside of his home as well. Growing up in Richmond, Freeman went to McGuire’s University School. The school headmaster regularly lectured Freeman and his classmates about how to model their moral conduct based on General Robert E. Lee.

At age 15, Freeman entered Richmond College, later known as the University of Richmond. He joined the staff of The Messenger, the university's literary magazine, and he was a college correspondent for the Richmond News. As a college student, Freeman celebrated General Lee’s birthday every year. Freeman graduated from Richmond College in three years, and then received his PhD from Johns Hopkins University.

Freeman’s fascination with the Confederacy would only continue as an adult. When he was twenty-two years old, Freeman worked an unpaid job sorting papers at the Confederate Museum in Richmond. In 1911, aged 25, Freeman obtained documents containing wartime messages from Robert E Lee to Jefferson Davis from June 1862 to April 1865, which had been believed to have been lost. He used these texts to create his first book, “Lee’s Confidential Dispatches to Davis,” which was published in 1915.

That same year, Freeman started writing a biography of Robert E. Lee. He initially planned it to be 75,000 words, and he thought it would take two years to complete. But instead, he wrote over 1,000,000 words across four volumes. The final volumes were published in February 1935. The work won him his first Pulitzer Prize.

The biography was critically acclaimed by national media like the New York Times, who called it “Lee Complete For All Time”. This work played a significant role in spotlighting Freeman as a public figure. But some people have criticized his biography for sympathy towards Confederate subjects.

AYERS: So, I think that Freeman would have thought that what he was doing was celebrating a great American hero. And obviously, it’s a bestseller and it’s -- people have read it for every generation since. And obviously it’s the same thing that he could write about George Washington, four volumes and win the Pulitzer Prize shows that it's kind of the same strategy. Let's take a great Virginian and elevate him to national significance. So that is what he did.

I don't believe he would have considered himself a propagandist. He would have considered himself a historian. But the, but the -- it's for that reason all the more effective at kind of a Lost Cause propaganda.

CONSTABLE: In addition to his historical research, Freeman worked as a journalist. In 1915, he became the editor of the Richmond News Leader, a newspaper that has since merged with the Richmond Times Dispatch. Along with publishing editorials, Freeman gave daily radio broadcasts each morning, where he would explain his views about current events.

Freeman occasionally used his editorials as a way to discuss the Confederacy. In one editorial in the Richmond News Leader in June of 1932, Freeman wrote about the history behind the Robert E. Lee statue on Monument Avenue in Richmond, describing it as "a fit memorial to the matchless Lee."

Elsewhere in the editorial, Freeman explained that once the Union Soldiers left Richmond after the Civil War, “Civil rule returned."

[music plays]

Nicole Maurantonio, a professor of Rhetoric and Communications studies and one of the founding faculty members of the Race and Racism Project at the University of Richmond, believes that Freeman’s belief system fits into a broader form of racism called the Virginia Way.

NICOLE MAURANTONIO: When we talk about his place within history -- it's not necessarily as simple as one might think. In that, kind of, the form of racism that I would argue that Freeman was really a part of is a, kind of a larger mentality that was known as the Virginia Way. Which is a kind of genteel paternalism, as some scholars have argued, that didn't really see Black people as capable of self determination.

But really saw himself as one who was acting on behalf of Black people and making decisions that he believed would be in the interests of Black people. But rather not truly invested in desegregation.

So Freeman's work, I'd say, was of the sort where he was certainly contributing to the racism of Virginia and Richmond specifically. But the ways in which he articulated it perhaps weren't as overt as one might expect or see in other sites across the South. So that became a kind of characteristic of Virginia specifically.

And like I said, that was referred to as the Virginia Way.

CONSTABLE: In his 2002 biography of Freeman, David Johnson argues that for Freeman, “respect for General Lee and Devotion to the Confederate cause did not equate to racial prejudice.” Freeman was a member of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation. In 1922, a Klansman delivered a warning to Freeman to attempt him to stop publishing his anti-lynching editorials, a request which he rebuffed. Freeman also stopped the tradition of separating the sports scores of Black colleges from white colleges in the Richmond News Leader. In 1947, Freeman put a photograph of African American civil rights attorney Oliver Hill, who was running for school board, on the front page of the News Leader. This, according to Johnson, “defied convention.”

However, University of Richmond history professor Pippa Holloway argues that small gestures like these served as a vehicle to preserve larger structural racism in Virginia. Holloway, who holds the title of Douglas Southall Freeman distinguished professor of history at UR, expands on this idea:

PIPPA HOLLOWAY: But yeah, he thought that there should be an order, society -- this is what most elite whites at the time -- they called it the Virginia Way here in Virginia. Basically, they believe that white people should govern and rule.

They believed, they would have said something like, “Well, we believe we were the ones best positioned to do this fairly,” or something like that. So they thought that -- they were a little bit critical of other states. So like, they would look at other states where there were a lot of lynchings and a lot of murders and a lot of racial violence.

And they would sort of say proudly, “Well, that's not the Virginia Way. The Virginia Way is a way of peace.” But what they meant by that was maybe not, um --. For example, “We shouldn't have lynchings,” they would have said, “but we definitely have to make sure that the state punishes people for crimes. State lynchings are extralegal violence; we believe that legal violence is fine.”

So they would have supported, for example, in Virginia back then the death penalty was around -- they use the death penalty for people convicted of sexual assaults. And this was used very much in a racial way. So they would use this to target African Americans, convict them of sexual assault and then -- then kill them with the death penalty.

And he would have said, “Well, that's great. That is perfect, because that keeps the peace. What you don't want is lynchings.” Because lynchings are mob violence. And they found that very distasteful.”

CONSTABLE: Freeman held many public beliefs that back up his support for the Virginia Way. He supported the poll tax, a Jim Crow era tactic designed to prevent African Americans from voting. He once wrote, “Shall we extend the franchise in Virginia by abolishing the prepayment of poll taxes as a prerequisite to voting? No, a thousand times, No!”

Freeman also supported segregation. When asked about whether the president of Virginia Union University should be invited to an awards ceremony, Freeman said “I do not feel that we ought to embarrass anyone or raise any questions by having a colored man at a dinner.”

But while Freeman held beliefs that clearly disenfranchised Black people, some of his writings portray perspectives that oppose racist attitudes, Holloway said.

HOLLOWAY: I know, for example, that Freeman thought some of the most virulent racists were causing trouble. There was an effort in Virginia in the 1920s to have extraordinarily rigorous policing of racial boundaries through what they call the one-drop rule. If you had one drop of non-white blood in you -- if your great, great, great, great grandparent was not white, then you're not white.

And there was this movement in the 1920s Virginia to make sure there was never going to be any racial mixing. And, and Freeman said, like, “Well, that's a little much, you know,” he said, “That's, that's not going to bring about the peace. We're sort of focusing on the wrong thing here.”

CONSTABLE: However, Holloway says that these denunciations of more blatant racist attitudes did not excuse him from his own.

HOLLOWAY: So his racial liberalism, sometimes -- or his views about race sometimes led him to denounce the most extreme racists of white people. But he would do it in a way that kind of furthered his own agenda of racial hierarchies and racial segregation and racial separation.

CONSTABLE: Part of Freeman’s racial agenda was the advancement of Lost Cause ideology, which justifies the South’s motives and involvement in the Civil War. Julian Hayter, a historian and a professor of leadership studies at the University of Richmond, says that Freeman’s work helped strengthen Lost Cause ideology and the memory of Confederate figures long after the war.

JULIAN HAYTER: The Lost Cause is made up of several elements, right? That, the, you know, that slavery was a benign institution; that states’ rights caused the Civil War and not slavery; that anybody who fought in defense of that system or died in defense of that system did so for a noble cause, right? And that ultimately the people who led those individuals were heroes.

You’ve got to recognize that people who lived through slavery saw -- wouldn't have seen liberty and slavery as incompatible. They would have saw slavery as a necessary element to their freedom, right?

So -- and slavery wasn't an addendum to the Southern way of life. It was central to it, right? It was central to their culture, was central to the economy, was central to their politics.

The master-slave relationship dictated all things Southern. Southerners are not lying when they’re telling you they’re going to war in defense of their way of life -- they were. Especially those who owned slaves.

What Freeman does in his biography of Lee is reaffirm this idea that Confederate leadership were heroes who were dying and who were serving in defense of their way of life.

CONSTABLE: Hayter argues that Freeman’s version of historical events resulted in damaging revisionism done to strengthen the images of Confederate leaders like Lee.

HAYTER: He, in a sense, was almost single -- not single handedly but very important in the, kind of, hero application of Robert E. Lee after the Civil War, right? These are the -- these are the -- like this is classic Confederate revisionism -- neo-Confederate revisionism, during the Jim Crow era -- which serves to not only paint the South and people who fought in defense of slavery in the best possible terms, they're doing that in some way so they can control the present.

If all these guys were heroes who fought in defense of a noble system, then the enemy is the North, right? And Reconstruction. So this serves a political purpose.

These histories in some ways are trying to clean up the image of these men who are responsible, in effect, for the deaths of six hundred sixty -- seventy five thousand people in defense of a system. This is propaganda, in some ways, to try to worship and have other people worship the memory of men like Robert E. Lee, who fought and died in defense of an ignoble system.

CONSTABLE: Freeman’s other work at the Richmond News Leader across a wider variety of subjects also helped to make him a powerful and influential figure locally, Maurantonio said.

MAURANTONIO: Freeman was a very prolific writer, writing thousands, ultimately, of editorials over the course of his career at the Richmond News Leader. And really, he had opinions about everything from gender, to race, to class. Freeman literally wrote about pretty much every corner of life within the city of Richmond and was ostensibly a thought leader.

And so when we think about his role, too, he was not somebody who was writing a lot, but he was somebody who people listened to.

CONSTABLE: But Freeman’s words had an impact far beyond Richmond. He had friends in high places, most notably former President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who credited Freeman for his political career.

Eisenhower was also a fan of Freeman’s work, even going as far to say “I am such an admirer of Dr. Freeman that I am always disposed to conform instantly to any suggestion he makes.”

Maurantonio spoke more about the way Freeman was able to capture such a large audience.

MAURANTONIO: And so I think that's important as well when we think about reception and audience and that Freeman had a big audience. And so when he was making these sorts of claims -- again, perhaps not as overtly racist as you may see in other documents and coming from other leaders, both within the journalistic community, but in politics more broadly.

Freeman still was doing that work, like I said, in perhaps just some more subtle ways. And so we see that racism kind of lurking beneath the surface of the things that he was saying.

CONSTABLE: Freeman appealed to his wide audience with his personality as well as his writings. According to an article published by The Collegian in 1978, one of Freeman’s biographers describes him as “the archetypal Southern gentleman — elegant, eloquent, honest, courteous and fiercely loyal to tradition.” His image was a large part of his national fame and success.

Exhibiting his admiration for Lee, Freeman focused on similar traits in the ways that he portrayed Lee's character.

AYERS: Robert E. Lee was widely admired in the North and in some ways was more popular than Grant, who actually wins the war.

And so, you know, Lee gets credit for being a gentleman, for being a Christian, for being principled, for defending his home. And it's interesting how -- just to set aside the fact that he broke his oath to uphold the Constitution of the United States -- that we can look past that because he was fighting for his home. You know?

And so I think that what Freeman did was to put this into a form that all Americans, all white Americans could read and admire. If he’d been sort of, you know, more obviously partisan, then he wouldn't have been able to persuade people.

Instead, he was talking about the character of Robert E. Lee. And I would say, you know, being out talking about Lee a lot myself, I find that that is what people still want to talk about. That he was a good person. But what I say was, 'What would have happened if he’d won?'

HAYTER: This guy was not just some random scholar tucked away in a dark office in some dusty campus, you know, campus building. This guy was a major media figure with a productive, a hyper productive legacy. So these ideas generate beyond at the academy, and beyond social elites, throughout the South and become widely accepted.

[music plays]

CONSTABLE: Freeman’s legacy is entwined with the University of Richmond. Not only was he a graduate of UR, but Freeman’s reputation and professional accomplishments make him one of the school’s most well-known graduates, according to Ayers.

AYERS: I’d say that by most measures, people would have considered him our most illustrious alum. So he graduates from here at 18 and then gets a PhD at Johns Hopkins at twenty two, wins the Pulitzer Prize twice, is the editor of the largest newspaper and runs a radio show that everybody listens to, and is friends with Douglas MacArthur and George Marshall.

And so, you know, by those objective measures, he's a distinguished alum. I think that that's, so that’s why they did. That’s why there’s a high school in Richmond named after him and so forth.

Another way of thinking about it, though, is why he was so popular, is that he was telling white Virginians what they wanted to hear, very much. And I think that his books on Robert E. Lee are really foundational for the Lost Cause. They elevate Lee as a virtually flawless man who -- who acted out the highest motives. And he also, while he would have considered himself friendly to African Americans, defended segregation very vigorously.

So I think that if you just look at it -- and of course, that he was rector of the board for a long time. So, you know, by measures of an alum, leadership at the University, accomplishments that were recognized this time on the cover of Time magazine.

So he was a national figure. That's why -- that people chose to honor him in the 1950s and 60s.

CONSTABLE: In 1983, Freeman’s daughter, Mary Tyler Cheek, and her husband created the Douglas Southall Freeman Chair in History at the University of Richmond. Since then, the Chair’s million dollar endowment has sponsored visiting professors from different universities every year. In 2020, Professor Pippa Holloway became the first permanent Douglas Southall Freeman Distinguished Professor at the University of Richmond.

Acknowledging that Freeman was a person with many layers, Holloway noted his success as a news editor and says that he was "not the worst racist in Virginia during that time period." She said his gradualist views in regards to race were, at the time, "sort of vaguely liberal." That being said, she noted that his legacy is problematic and expressed discomfort in honoring it through the professorship title.

HOLLOWAY: So on a basic level, it means that University of Richmond is honoring his family's intentions by hiring someone who honors his legacy. Obviously, Freeman is someone who has a really complicated legacy, and in many ways, a really problematic legacy, right?

He’s someone whose work was an element of the Lost Cause ideology; he’s someone whose work was celebrated, whose academic work, whose scholarship on Robert E. Lee and Lee's lieutenants and so on, was part of the construction of the Lost Cause mythology, which celebrated slavery in various ways.

And so his work as a person is someone that, in many ways, neither I -- I mean, I certainly don't want to honor or remember, right? This is not, this is not a history that I particularly want to celebrate.

I don't think we should be celebrating someone, you know, the Lost Cause. And the whole -- all the work that he did has brought murder; it's brought pain; it's brought exacerbations of racism. So there is definitely a problem with honoring his legacy in that way.

CONSTABLE: Honoring Freeman's legacy, however, is not unique to UR. Just outside of the city of Richmond in Henrico County, Douglas Southall Freeman High School teaches about 1800 students each year. In 1954, a year after Freeman died and the same year that he was posthumously awarded a second Pulitzer prize for his biography of George Washington, the high school opened, bearing his name.

Like Holloway, the school's principal, John Marshall, has mixed feelings about his school’s namesake and admits it does not come without controversy.

JOHN MARSHALL: I think there's some pride in our school that we’re named after a scholar, right? That we’re named after a writer, a historian, a journalist. You know, not after like a celebrity or politician or anything like that; just named after someone who exercised the pursuits that we -- you know, good writing, good communicating, thoughtful commentaries that we have today -- that we would want to instill in our students.

Certainly not without controversy -- Dr. Freeman, not controversial at all during his day, which is pretty impressive, given how much, how many words he wrote. But judged by the, you know, 2020 standards, someone who, who spends half his life writing about Robert E. Lee and his generals, you know, and quite likely admired the military strategy of Robert E. Lee, you know -- that's certainly something that we would be, we'd be remiss not to discuss and talk about as a school, which we do openly.

CONSTABLE: In August of 2020, Marshall announced that they would be changing their mascot, the “Rebels”, after concerns over the nickname’s Confederate connotations.

MARSHALL: Our mascot was kind of an old, cranky Confederate soldier throughout the 50s 60s and 70s. The Confederate flag was prominent in the 60s and 70s. Even into the 80s. So that rebel ties to the Confederacy, I think, are pretty, pretty clear historically.

Since that time, right, in the last several decades, we've moved away from any ties to the Confederacy with the word “rebel.” But you can't deny the fact that it was part of the part of the school's history.

CONSTABLE: Marshall says that feedback from the school community was a driving force behind the decision to retire the mascot. Over the summer of 2020, the school sent out a survey to ask the community for their opinion.

MARSHALL: We were blown away by the response. Thousands of responses, some people, you know, articulating how what the word rebel really encapsulates their fond memories of Freeman.

But really -- blown away by the powerful individual responses that said, “Here's how I experienced the word as an African American student, or as a community member that drives by and wants to send my kid to the school one day.” And so once we read those, we brought a committee together to help me interpret what we found to make sure it wasn't just me. I’m just the steward of this position. Some longtime Freeman supporters, some future Freeman parents, some current students, [continues to next quote]

And we decided almost unanimously that there's -- that the right thing to do was to retire the name “Rebel” and look for a new one.

[music plays]

CONSTABLE: The conversations happening at Freeman High School are not outliers. In a time where information is so easily accessible, legacies are constantly being reexamined and rehashed. In the next episode, Jackie Llanos will look at memorialization at UR and student governments’ continued quest to rename Freeman and Ryland Halls. How much power does the name of a building hold? Can memorialization take on a life larger than the one it remembers?

Professor Maurantonio says that memorialization should lead to questions and conversation.

MAURANTONIO: Well, I think when a building is named after an individual, generally what that says is that the institution or the organization deems that individual is important. And so certainly a significance is imbued. So that, of course, begs the question, why is that person significant? And so, for what reasons is that person being remembered?

CONSTABLE: As for Freeman, his story at UR is far from over. With the release of UR’s investigation, campus conversations about him, Robert Ryland, and others will return to the spotlight.

In his interview with us, Ayers describes Freeman as “an embodiment of his time”. As times change, it is important that we continually reevaluate history and the legacies of those who came before us. When someone like Freeman has their name on a building and a professorship, and is strongly connected to the University, it is even more vital that we look at the implications of their name.

MAURANTONIO: He was recognized -- he was seen as somebody who was important, who was a thought leader, who had opinions that mattered. And so in some ways, it's not surprising that his name would be on a building at the University of Richmond, given Freeman's connections.

But it does beg questions as to what it means for us. And that meaning may change and has changed, likely, over time. And so I think tracking those changes and tracking what the meaning of Freeman has been and continues to be is incredibly important for us.

CONSTABLE: With that, we’ll see you next time.

[music plays]

This episode of Beneath the Surface was narrated by me, Gedd Constable.

The story was written and reported by Mia Lazar and me.

Additional reporting was provided by Grace Kiernan and Nina Joss.

The story was edited by Nina Joss.

And our music, as always, was graciously provided by Nathan Burns.

Additional sources that contributed to our reporting:

Douglas Southall Freeman on Leadership. By Douglas Southall Freeman and Stuart W. Smith. Edited with Commentary by Stuart W. Smith; Foreword by James B. Stockdale. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Pub. Co., 1993.

Douglas Southall Freeman. By David E. Johnson. Gretna, La: Pelican, 2002.

George Washington: A Biography. Volume VI, Patriot and President. By Douglas Southall Freeman. Foreword by Dumas Malone. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1954.

The Last Parade; an Editorial from “Richmond News Leader” of Friday, June Twenty-Fourth, Nineteen Hundred and Thirty-Two, the Last Day of the Forty-Second Annual Reunion of the Confederate Veterans. By Douglas Southall Freeman. Richmond, Va: Whittet and Shepperson, 1932.

Memoranda Concerning Douglas Southall Freeman for Private Distribution to Members of Civil War Round Tables and a Few of His Friends. 1967.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now