This Collegian UR podcast explores the life of Robert Ryland and how he perpetuated systemic racism and slavery in Richmond and the U.S.

Hosted, edited and produced by Grace Kiernan. Nina Joss assisted in editing. Music created by Nathan Burns. Podcast art created by Nolan Sykes and The Collegian.

Listen on Spotify | Listen on Podbean

GRACE KIERNAN: When the Confederate monuments that once towered over the center of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, started to come down in June 2020, the moment reflected a larger shift that had been building across the country. Americans were starting to think about the people exalted by monuments, the names engraved on the buildings they entered — they were starting to question who those people were, why they are honored, and whether they should be.

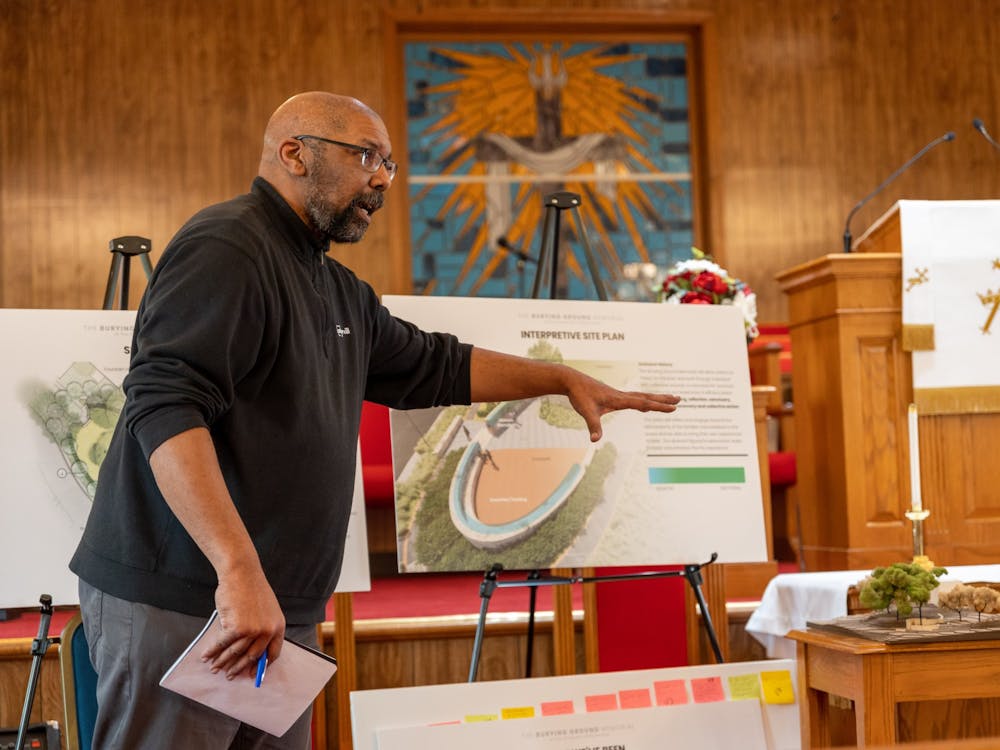

The University of Richmond has not been immune to this movement. In 2019, UR acknowledged the Westham Burial Ground, where enslaved people are buried on its campus, launching a university-wide interrogation of its history regarding race, racism and memorialization. As part of this interrogation, rumblings about certain names commonly heard around campus began, and never stopped.

One name that has been uttered over and over at UR is “Ryland.”

Ryland Hall is the oldest building on UR’s campus. If you look for it today, you might have an easier time recognizing it by the surrounding construction equipment. Currently, Ryland Hall is undergoing a $25 million renovation and expansion. But until last fall, the hall looked much the same as it did when it was built in 1914 as one of four original buildings that made up Richmond College, after the college moved from its original city campus to its current location in Richmond’s West End.

Originally known as the “Academic Building,” today’s Ryland Hall actually has two namesakes. Most associate it with the founder and first president of Richmond College, Robert Ryland. Part of the hall is named in his honor, in part to commemorate his generosity which helped keep the college alive during the reconstruction period, according to the University of Richmond website. But the third floor of the western wing, which is the picturesque library often shown on social media and tours, is Charles H. Ryland Hall. Charles Ryland was Robert Ryland’s nephew, and served as trustee, treasurer and librarian of Richmond college. He died shortly before the West End campus was opened, but his daughter, Marion Garnett Ryland, followed in his footsteps and became the first librarian at the new campus.

So why are people talking about Ryland Hall today?

Concern lies more with Robert Ryland than with his nephew, Charles. At the same time the elder Ryland was serving as Richmond College’s president, beginning in 1841, he was also the pastor at the First African Baptist Church in Richmond, whose membership was made up of enslaved and freed Black people. Ryland owned enslaved people himself and expressed conflicting views on the institution of slavery and its victims through his evangelical work.

In fall of 2018, UR president Ronald Crutcher charged his Presidential Commission for University History and Identity with investigating university history and its implications for our current campus climate and the future. In 2019, that Commission recommended that a further investigation and report be made about Robert Ryland, Douglass Southall Freeman and the Westham Burial Ground, according to a document outlining the commission's recommendations. The document also states that President Crutcher might form a separate commission to consider making a recommendation to the Board of Trustees for the possible renaming of Freeman and Ryland Halls.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

On Oct. 30, 2019, president Crutcher released a letter to the university community that stated that the research on Ryland and Freeman had commenced. On Feb. 25, 2021, president Crutcher sent an email to the UR community that included the report on Freeman and Ryland, as well as updates on the renaming decisions. In this email, he announced that the name of Ryland Hall would not be changed, but that the terrace of the new Humanities Commons would be named after a person or people who were enslaved by Robert Ryland.

In this episode, we will be discussing Robert Ryland's legacy at UR and within the city of Richmond in response to ongoing conversations about his memorialization on campus.

I’m Grace Kiernan and this is The Westham Project on Beneath the Surface, a Collegian podcast.

[music]

Before we dive in, it is important that we take a moment to acknowledge our inherent shortcomings in the creation of this podcast.

The Collegian is a predominantly white institution on campus, and we are aware that this lack of ethnic and racial diversity on our staff, specifically regarding our staff’s lack of Black representation, will have an effect on how we report this story.

As The Collegian strives to serve its stated mission of reporting the truth accurately and inclusively, we believe it is important to be transparent in this shortcoming and reemphasize our dedication to improving our organization in all areas of diversity, equity and inclusion.

KIERNAN: One of UR’s recent presidents, current professor of American Studies and co-chair of the Presidential Commission for University History and Identity, Ed Ayers, is a historian of the 19th-century American South and has encountered Robert Ryland in his research more than once. In fact, in 2013, Ayers gave a talk about Ryland’s story at the Virginia Baptist Historical Society’s annual meeting.

Ayers chose Ryland as the focus for his talk because of the challenge and opportunity for reflection that Ryland's character presented, he said.

EDWARD AYERS: How could that not be an interesting challenge — to be a slave-holding Christian minister overseeing First African Baptist and creating the college? Right? So I didn't, I just went into it as an exploration, and you can tell from from the end of it, it is kind of a reflection on our — how do we think about our own complicity in the wrongs of our time.

KIERNAN: Ayers’s talk covers much of Ryland’s life, noting that Ryland grew up on a farm with enslaved people, but that he chose to pursue an education rather than inherit the farm. He did inherit enslaved people, nonetheless.

AYERS: But in a city, people and this is Ryland's particular position in all this. So he’s an urban man. He doesn't have a farm or plantation no matter what he was. He took an education instead of a farm with his father, said you can have one or the other. And he said, I'd rather take my inheritance as an education. So he goes to Washington, to Columbia College, I think it's called. And so he inherits some of the enslaved people from his father, but he rents them out, including to the college.

KIERNAN: Ayers underlined the importance of understanding context when it comes to dissecting history and, to consider Ryland’s legacy, he said that you also have to consider his environment.

AYERS: And so if you came to Richmond in the 40s and 50s, you'd have seen slavery with a profile unlike anywhere else in the United States. Very large numbers of enslaved people working in factories, factories, working at the Treader Iron Works.

And that would have been hired out and finding their own place to live. What they had to do is give almost all of their wages to owners. So that's not what we pictured slavery being like, right?

KIERNAN: Ayers pointed out how this made UR's path of reconciling with its history unique from other institutions in the area. While other universities owned enslaved people, the University of Richmond did not, he said. Ryland did, however, employ the labor of enslaved people he owned at Richmond College, according to Ayers.

AYERS: And so compared to other colleges and universities, like UVA, or William and Mary, the university does not own enslaved people. Right. And so, and was not built by enslaved people. So that's why compared to the two places I know well, on either side of us, UR has a different path through all of this. Right. In the report that we wrote for the commission, we called it a deep but oblique connection to slavery. So this doesn't remove any burden. It just says that we have to know what we're talking about.

KIERNAN: Like many white southerners in his time, Ryland was a slaveholder. Living in what would become the capital of the Confederacy, his connection to slavery was an undeniable and commonplace situation. And Ryland often expressed, in his own writing, pro-slavery and pro-Confederacy views.

But Ayers also explained that, before the Civil War and slavery abolitionism movement, it did not seem like slavery would end. The institution of slavery was modernizing right alongside industry.

Ayers positions Ryland and his pastorship at the First African Baptist Church within that context.

AYERS: So this [slavery] is not an archaic system. It was deeply implicated in all structures of capitalism and so there is so much more insidious even because we can see that it was showing no signs of fading away. I describe it, and this seems even more apropos today, like a virus, it could adapt itself to any different context.

And that's what Robert Ryland shows us.

[music]

KIERNAN: Ryland’s connection to slavery gets more complicated when we consider his position as the first pastor of the First African Baptist Church. While the tone in which he wrote about Black people, both freed and enslaved, often reflected a feeling of white superiority, he was not in full support of the limitations that slavery placed on Black people’s religious experiences.

AYERS: You know, you read his autobiography he wrote in the 1890s, which, you need to be careful about that, because he can remember it in ways that are flattering — but he actually says something funny. He says it was illegal for Black people to preach.

But he said, ‘But in our church, we had some very long prayers.’

Right so — and he recognized that the congregation did not come to hear him. They — he said they actually had to start locking the doors so the people wouldn't come late after he was done talking so they could hear each other preach. Right.

So I think one of the things we need to imagine is turn this around and imagine it from the perspective of enslaved people themselves. Rather than what did white people do to Black people is: How did Black people make lives for themselves in this inhumane and unjust system? And in that context, First African Baptist is one of the most important institutions in the city.

So you see some people say, ‘Robert Ryland preaches the slaveholder’s gospel.’ And other people are saying, ‘I believe he's an abolitionist.’ So, you know, that gives you some idea of the moral complexity.

And I think the trick for us as we think about all this is how complex doesn't let anybody off the hook, that that is not an extenuating circumstances. It's just to say that if we actually thought about our own lives, we would realize that we're living in complexity, too.

KIERNAN: Ryland’s extensive writing and the accounts, often his own, of his behavior at the First African Baptist Church are sources of controversy when it comes to pinning down his role in upholding slavery.

AYERS: Ryland, you know, baptizes over 3000 people. You know, he's criticized for being an abolitionist. You know, he's criticized for teaching Black people to read with this catechism. On the other hand, when challenged, he says, “I believe that slavery is appropriate, for the current circumstances.”

KIERNAN: And the catechism is a complicated thing, too. In Christianity, a catechism is typically a set of questions and answers that summarize religious principles. In this case, as Ayers said in his 2013 talk, Ryland had written, “a catechism of fifty-two lessons for his Black congregation, with yes-or-no answers, that reinforced the duty of slaves to obey their masters.”

And yet that same, paternalistic, pro-slavery catechism concerned then-Richmond Mayor Joseph Mayo, because he saw it as, “an invitation and an aid to help slaves learn how to read,” according to Ayers. Teaching enslaved people how to read was, at the time, illegal.

13 In this same 2013 talk, Ayers quoted Charles Irons, Elon University professor of history and chair of the department of History and Geography, in discussing the relationship between Black Virginians and churches in the mid-1800s. Here’s how Irons characterized it:

“If they,” — meaning Black Virginians — “did submit to some sort of nominal white religious oversight and seek membership in an evangelical church, enslaved Virginians reinforced whites' belief that slavery was a benign vehicle for Christianization. If they instead rejected the mission as pro-slavery garbage, bonded Virginians only offered more proof that slavery was necessary — that Blacks needed more time in the refining fire of slavery to come to a saving knowledge of Jesus.”

We spoke to Irons to learn more about Ryland, the First African Baptist Church, and the relationship between slavery and religion in the mid-1800s South.

CHARLES IRONS: One of the worst storylines in American history is the enslavement of, by 1860, four million men, women and children by a people who considered themselves among the most godly upon the face of the earth.

And so this seemed like a really specific and concrete variant of the why good people do bad things, and one that had enormous personal relevance as someone who grew up in the United States south.

So, it was very natural to focus on the relationship between Black and white evangelicals to try to understand how whites who were justifying Blacks’ enslavement through scripture related to those same men and women, within the context of their own churches.

KIERNAN: The significance of First African Baptist Church is what originally drew Irons to study Richmond’s evangelical history more closely.

IRONS: I mean, Ryland and Richmond may not be completely unique, but First African Baptist is really amazing. I mean, it is among the very biggest Protestant churches in the world by 1860. With over 4000 members, so it is remarkable. I mean it is a mega church before mega churches were a thing.

So, I fell in love with First African Baptist before I encountered Ryland, but anyone who encounters First African Baptist has to encounter Ryland, as the white-approved leader of the congregation.

KIERNAN: White-approved leader did not just mean that white Baptists had supported the selection of Robert Ryland as the first pastor at First African Baptist Church. It means they had appointed him.

IRONS: I'm not sure how much free will that Black Baptists actually had in choosing Ryland. Rylands' own language is that he is chosen by both whites and approved by Blacks. And this is a formulation that certainly would make sense to him, but the essential element was that white Baptists and First Baptist Church, out of which Black members went, in 1841, to form First African Baptist, the key ingredient was white approval.

KIERNAN: The First Baptist Church was, from its founding in 1780 up until 1841, a multiracial church. White slaveholders brought enslaved people to church with them. At a certain point, the members of the congregation decided to separate, and created First African Baptist Church for the Black members of the congregation. It was overseen by white Baptists and First Baptist Church, but became the first Black church in Richmond.

IRONS: From state law after 1831, Black churchgoers could not worship independently and needed white supervision. When First Baptist set apart men and women to form First African Baptist Church in 1841, they also put in place the leadership structure. So they also formed a committee of white Baptists from across the city that would provide governance, and they also named Ryland as the Minister.

[music]

KIERNAN: Deborah Booker, the current historian and archivist for First African Baptist Church, has gathered and read through the First African Baptist Church journals, Ryland’s writings, and much more over the past decade.

DEBORAH BOOKER: First African was special because it was an experiment. Some of the reasons given for the split of the First Baptist congregation, were the size of the church was too small for the growing number of colored people who were attending the church with their white owners. Another reason was the two groups of people sat in different places in the church with the ruling class, sitting on the sanctuary floor and the enslaved class sitting in the balcony. And therefore, the enslaved people could not be reprimanded by their owners if perceived offenses were committed. Another reason was that the two groups of the congregation worshiped differently. The African Americans worship more interactively and the ruling class, sat quietly and would nod, but not comment.

KIERNAN: Booker’s account comes from, in part, a book called “First Baptist Church Richmond, 1780-1955: One Hundred and Seventy-Five Years of Service to God and Man,” which compiles the records from the Church for those years.

Teresa Payne, who graduated from UR in 1974, wrote an honors thesis titled: “Robert Ryland and the First African Baptist Church of Richmond: their antebellum years,” and found a similar explanation for the split. First Baptist Pastor Jeremiah Jeter, according to Payne, listed a lack of space for accommodating the Black members of the congregation as a major reason for the split. Jeter also believed that the white members and Black members of the congregation would benefit from different preaching approaches.

Despite Jeter’s reasons, Payne said that Ryland’s analysis of the situation more bluntly acknowledges that the underlying motive was likely a racist one. She includes that Ryland once wrote: "some very fastidious people did not like to resort to a church where so many colored folks congregated, and this was thought to operate against the growth of the white portion of the audience.”

BOOKER: Therefore, the men of the First Baptist recommended the split of the congregation, with the whites moving to a new church building on Broad Street and remaining congregants of color keeping the building on the corner of 14th and Broad streets. Now the experiment was to see if a group of enslaved and free African American men, women and children could prosper and learn the doctrines of the Baptist faith in decency and in order if governed by Caucasian deacons and clergy of the three Baptist churches in Richmond, and of course the three Baptist churches were all white. And the governing body was all white.

The experiment proved to be a success. Not because of the rule of the Caucasian governing body, but because the African American men, women and children proved themselves to be worthy of learning and following the Baptist doctrine, by governing themselves religiously and financially, and by showing themselves to be decent to the citizens of the city of Richmond, Virginia.

KIERNAN: Other accounts of the split present this story somewhat differently than Booker and Payne did. In February of this year, the Valentine Museum in Richmond published a blog post about the First African Baptist Church which said the split between the two congregations originated with a radical request made by the Black members of the First Baptist Church who wanted their own place to worship. The white deacons of the First Baptist Church eventually agreed and, to accomodate Virginia state law, which forbade independent Black worship or preaching, the new First African Baptist Church would have to have a white pastor and board, according to the Museum. Rather than framing the creation of the First African Baptist Church as a decision based off of space needs or racist views, the Valentine Museum’s post calls it, “an unprecedented undertaking that would lead to more unprecedented demands for autonomy, justice, self-governance, freedom and, eventually, the full rights of citizenship.”

Both accounts are probably true to an extent, Booker said. The version she is familiar with isn’t exactly contrary to what Valentine Museum has found, it just comes from a different perspective, she said.

BOOKER: When you’ve got someone who’s invested one side or the other, they’re going to not wrongfully state the facts, but romanticize and soften it, and find the humanity in one side more than the other.

KIERNAN: In the book “The First Century of the First Baptist Church of Richmond,” which Ryland wrote, he listed his reasons for accepting the position as its first pastor, and Booker summarized them aloud. First:

BOOKER: He had been preaching at the Lord's day to country churches, but their remoteness was sometimes inconvenient requiring his absence from home and college for about two days of the week. That was his first motive for accepting the position.

KIERNAN: Second:

BOOKER: The second one, he felt that the separation of the two classes would remove a great impediment from the path of the first church, and thus indirectly advance the prosperity in all coming time. And that he had no right to excuse himself from the duty of helping forward so important, and object.

KIERNAN: Third:

BOOKER: Number three. Since the passage of the law by the Virginia legislature forbidding all colored preachers to minister to their own people in Divine things. He, meaning Ryland himself, felt that all the ministers of Christ, and especially those of his own nominations are called on to put forth new efforts to evangelize people of color.

KIERNAN: Ryland saw slavery as a vehicle through which to convert a people who he viewed as inferior to Christianity, Booker said. Ryland believed that slavery was in the scriptures, and viewed it as a part of God’s plan. Ryland did, nonetheless, find some faults in the way American slavery affected the enslaved people.

BOOKER: According to his writings, it was not that he believed that slavery was a sin, but that some greivous sins were connected with slavery, such as the separation of husband and wife, the separation of parents from their children for mere gain, and the prohibition to teach colored children to read the Word of God. And in his mind, these were glaring wrongs. And I put glaring wrongs in parentheses because that came straight from the reading. He felt that it was not his responsibility to advocate against slavery, his responsibility was in teaching the Word of God. He felt that by learning the Word of God and becoming a Christian, the colored men would become more useful servants if they were in bondage, and more safe and reliable residents if they were free. Now, in saying that he, he did not really respect the colored man as an equal to the white man.

KIERNAN: Ryland seemed to view slavery as a natural state through which to indoctrinate Black people into the way of the Chrisitan Lord. His eventual vision, Booker said, was to send Black people back to Africa as Christian missionaries. In fact, the First Baptist Church did send the first American Baptist missionary to Africa. Lott Carey, an enslaved member of the First Baptist Church, sailed to Sierra Leone and formed a Baptist church there in 1821, two decades before First African Baptist would form and Ryland would begin preaching there.

While he sought to include Black people in practicing religion, Ryland’s paternalistic view of Black people comes through in much of his writing, and is notable in his characterization of the first congregation at First African Baptist Church.

BOOKER: In some of his writings he was very condescending in his opinion of just what the colored people of his congregation were capable of doing. It states that he was pleasantly surprised when he stood before them in the pulpit and found them to be neatly washed and dressed for church... He was surprised that they could sing in the fashion of the Baptist tradition and sing well. He was surprised that the members of his congregation understood finances, and were prompt in paying their debts.

KIERNAN: Ryland often uses the word “surprised” in his writing when members of his Black congregation seemed to show significant intelligence or morality. Although Ryland’s tone could be perceived as complimentary, the premise for those praises is the assumption that Black people are not equal to white people, or not as capable.

BOOKER: He was surprised by their generosity. He gave an example of the story of a woman in his congregation named Sophie who, upon seeing him one day, gave him a quarter and stated that, ‘Although she herself could not read. She wanted to give this donation so that others could be taught, and the gospel could be reached throughout the world.’ And he was stunned because a quarter was almost like $100 during that time, especially to a colored person.

KIERNAN: Booker emphasized the importance of the pastor role in Baptist churches, especially during that time period.

BOOKER: Ryland believed in slavery, but I think that, given the time, the times in which they lived, I think that he was fairly respectful of his congregants. And I think that they — see they were respectful of him in his position, I mean, they were, they were respectful of the man, but he was the pastor of their church. And that's, that's so different from the way it is now. It's like, you're not you might be the president of the United States, but and the people might not like you as the president, but they're respectful of the position you hold the presidency. So the congregants were respectful of his position. He was the pastor of their church.

KIERNAN: Other anecdotes, albeit written by Ryland himself, seem to confirm that some of the congregation did revere him in his position. And there are some ways Ryland seemed to be benevolent toward the members of First African Baptist, Booker said.

BOOKER: Now, having given these examples of how surprised, in what the colored members of his congregation knew, and knew how to behave and knew how to dress and knew how to, how to manage finances, let it be known that he often went a step further than what was allowed within the times in which he lived. He states that the laws of Virginia were very stringent as regards to colored men preaching, therefore to circumvent these laws, what he did was encourage the colored parishioners to pray in public, and he used members of his congregation to aid him during worship. However, he did place restrictions on them as to how the prayer should be given. You were not to whine, or fall or repeat yourself or grunt as he felt that these were vulgarities, and didn't serve the Lord well. He did allow a distribution of religious books, and he developed a kind of lending library. And these books were given to his congregation by the Virginia and foreign Bible Society. And he also circulated Bibles and testaments among the people of his congregation who could read and allow the people of the congregation, who could read, to read to members of the congregation who could not.

KIERNAN: Ryland’s behavior is not always easy to understand. Booker’s account of him, like most, does often rely on Ryland's own writings. And personal accounts are often flattering. Compare it to what one of his congregation members had to say about him. The famous Richmonder, Henry "Box" Brown, known for having himself shipped in a box to allies and freedom in Philadelphia, had once been a member of First African Baptist. This is what he wrote about Ryland:

“The Rev. R. Ryland, who preached for the coloured people, was professor at the Baptist seminary near the city of Richmond, and the coloured people had to pay him a salary of 700 dollars per annum, although they neither chose him nor had the least control over him. He did not consider himself bound to preach regularly, but only when he was not otherwise engaged, so he preached about 40 sermons a year and was a zealous supporter of the slave-holders' cause; and, so far as I could judge, he had no notion whatever of the pure religion of Jesus Christ. He used to preach from such texts as that in the epistle to the Ephesians, where St. Paul says, "servants be obedient to them that are your masters and mistresses according to the flesh, and submit to them with fear and trembling"; he was not ashamed to invoke the authority of heaven in support of the slave-degrading laws under which masters could with impunity abuse their fellow creatures.”

Brown’s charges do not change the content of Ryland’s story, they just expand its meaning and interpretation beyond Ryland’s view of himself. Brown’s account is one of few, if not the only, available versions of Ryland’s pastorhood told by an enslaved person. Opinions weren’t kept in the church journals, Booker said. And it would have been incredibly risky to write anything negative as an enslaved person, assuming you could even read or write. So we heavily rely on a white version of history.

BOOKER: When, when writing your own history, you tend to romanticize, and give a good thing. But I believe, and he, Ryland did state that he stuck to the doctrines of the Bible and yeah and I do remember reading that, if, if the topic of slavery came up that he would then invoke or, you know, ecclesiasies or whatever, whatever texts he could find to not promote slavery, but to sell it as ‘This is the way of the world is not a bad thing if it's in the Bible, how could it be, how could it be bad?’ He felt that slavery was the way that the white man could teach Christianity to the native in Africa but before going to Africa, they had to teach the doctrine of Christianity and the Baptist faith to their own to their own people, enslaved here in America.

KIERNAN: Eventually, things began to change. Ayers said, in his 2013 talk, that in April 1865 Black federal troops marched into Richmond and barred Ryland from preaching at the First African Baptist Church. He had expressed pro-confederate views throughout the War, mainly regarding the maintenance of Southern independence, but had also urged the enslaved people in his congregation to stay with their owners. The members of the church convinced the federal troops to let Ryland back into their Church, Ayers said. According to Ayers, Ryland wrote in his memoirs that, at the end of the Civil War, when the church’s rules were modified to allow Black people to practice religion independently, he resigned “from a belief that they would naturally and justly prefer a minister of their own color.”

This account is different from what Booker has found written in the Church journals, which says that Ryland was succeeded by another white pastor right after the conclusion of the Civil War. George H. Stockwell was pastor for just over a year before his associate pastor, James Holmes, became First African Baptist’s first Black pastor, Booker said. Booker wasn’t sure what the exact circumstances were with Ryland’s departure from the church, but noted that the transition from white to Black pastor was revolutionary.

BOOKER: When the governance of the church was finally turned over to the African American congregation, and an African American minister was allowed to serve as Pastor, the congregation was elated and deservedly so. They revered their first African American Pastor Dr. James Holmes, and felt that they were no longer being scrutinized, and could worship in their own way.

If you've never had a Black minister, you don't know what you're missing. So they probably did not know what they were missing until we had Dr. Holmes. And then it was like, Oh, it was like a revelation.

[music]

KIERNAN: One of the other members of First African Baptist, John Jasper, went on to start a new Black church, Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church, and it became one of the earliest independent Black churches in Richmond. Here’s Benjamin Ross, the current church historian and archivist:

BENJAMIN ROSS: Jasper, well, he was born on the Fourth of July 1812. Slave on a plantation and found his way to Richmond ... In fact, he was baptized in First African Baptist Church. But Jasper, you know, he had his religious experience. And then he embarked on a career as a preacher. And he preached all over Richmond, preached all over the state of Virginia.

KIERNAN: Jasper’s preaching career began in the First African Baptist Church under Robert Ryland, according to the Valentine Museum. Ryland would often call on one of the Black assistant preachers or deacons, elected by the Black congregants, to begin each service with an opening prayer which, according to the Valentine Museum, often sounded more like a sermon, and secretly allowed Black preachers to preach to Black congregants in Richmond, even though state law forbade it. One of these assistant preachers Ryland routinely called upon was John Jasper.

Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church has a rich history, but one of the things that really differentiated it from First African Baptist Church and other Black Baptist congregations at the time of its founding, was that it was founded by Jasper without white supervision. We asked Ross whether he thought that had an impact on the way the church developed.

ROSS: There probably is, because the churches that were organized with a white pastor, Black church that had a white pastor, the white pastor pretty much ran the order of service from the flight perspective, how the service would go, and it was probably very regimented in what we would call an order of service. You know, you did this, you did that, and the private wasn't much room, if any, for any religious outburst of singing and shouting, for example. Now, Black churches. Yes, there is an order of service, but there is also a recognition to allow Black people when they are caught up in the spirit to have some time to get caught up in that spirit and some time to calm down. I doubt it that white ministers allowed that even to happen.

I think if they were worshipping in a white church, then of course they were expected to what I'm going to describe as the white way of worshipping, singing of hymns and, and pretty much an order of service. Now when the Blacks got their own churches, I think they changed the worship a little bit more to their, more to their liking, which had a lot to do with their African roots. And that's when you might see a change and some of the music. Although they sang hymns for generations afterwards, they're probably--the introduction of slave songs, you know, spirituals and other songs that the slaves sang in the fields-- I've heard those songs in the church, that sort of thing.

KIERNAN: Even as Black congregations came into their own, and Black churches organized by and for Black people started to crop up, there was still the issue that Christianity was a faith not only forced onto enslaved people, but used time and time again to justify their bondage by white slaveholders.

ROSS: There was always that problem with the scriptures telling you to obey your masters and things like that, which was used heavily to keep you in line, because if the scriptures said obey your master, they’re certainly not going to argue with that. Well, I think people kind of said ‘Let's look at that scripture a little bit more closely to see exactly what it would mean if not ignore it altogether. [laughter] But today and in the 20th century, the 21st century, as a matter of fact, the Black church of the 21st century is nowhere near the Black church of the 19th century.

KIERNAN: Charles Irons, the University of Elon professor we heard from just a little while back, shared what he knew about the early Black pastors and their journey in trying to disentangle white supremacy from Christianity.

IRONS: One of the characteristics of this whole first generation of Black leaders is many of them, particularly in urban environments, trained under white leadership during an antebellum period in which part of the training was learning how far one could push whites and how far one, you know, needed to retreat into certain cultural expectations about white supremacy, learning those boundaries was an essential part of the training formal and informal. And so, that first cohort of leaders is administratively prepared to take on church leadership, but is still wrestling with this legacy of their of their training of their mentorship in a really paternalist white supremacist system.

KIERNAN: Irons said that Robert Ryland was part of enforcing that paternalist white supremacist system of thinking that he is talking about. Ryland did seem to work against the wrongs he recognized within slavery, but never saw the system itself as wrong.

IRONS: He accepted the basic unjust system of slavery and tinkered around the edges by trying to improve the ecclesial freedom and the access to literacy of some of the men and women whom he served by he did not do a thing. In fact, he probably supported, he definitely supported the overall institution of slavery, and instead of making us again just cast stones around I think we should think gosh what other unjust systems of which we’re apart, right now, we instead of trying to ameliorate we should be trying to overturn. And that's a really challenging and provocative question. I think it's easier to be less sympathetic to Ryland because, you know, half of the country, during his pastorhood, was clamoring that slavery was wrong. So he, it's not like he's just a product of his time right i mean he's a product of his place and time. And his racial context, but he was trying to tinker within an unjust system instead of overturn it.

KIERNAN: Ryland, according to Irons, is not the only Southern religious figure who seemed to have paradoxical views on the institution of slavery.

IRONS: I mean Charles Cole cartoons is the famous, famous example, who went to seminary in the north of Princeton, and was writing home ‘Oh my gosh slavery is an abomination in the sight of God it's morally wron’g and comes home determined to make a difference, and then realizes that is he says those things in his hometown, that he'll be run out of town on a rail. And so he softens and he tries to do all of the same things Ryland tries to do right catechism starts in my independent churches, but over the course of his career you can see him just hardened into a plain pro slavery ideolog. Whatever conflicts the man had at the beginning of their ministerial careers are compromised by where their paycheck is cut and their bread is buttered.

Because in fact all human beings are like that right, the very same people who do good things sometimes do bad things sometimes, and he was most definitely conflicted.

KIERNAN: Ayers’ 2013 talk details the end of Ryland’s time in Richmond:

“Robert Ryland lost everything in the war. In 1865 he had nothing left but $10 in gold and a good milk cow. To support himself, he sold milk on the streets of Richmond. The other institution to which Robert Ryland was committed, Richmond College, also lost everything in the Civil War. The trustees pledged the college’s resources, laboriously gained over the preceding thirty years, to the Confederacy. A fifth of the graduates of Richmond College died fighting for the Confederacy, and the college saw its buildings occupied by federal troops, its endowment rendered worthless, its books and apparatus scattered, its once booming city in ashes. After emancipation Ryland, stepping down as president, taught at a school for freed people in Richmond before moving away several years later.”

Irons has an interesting perspective on Ryland’s decision to teach at a school for freed people, which was organized by a Northern abolitionist, according to an article in Richmond Magazine called "God's Half Acre."

IRONS: I don't regard that as a step towards racial justice on Ryland's part. I regard that as actually a discouraging postwar convergence of northern white and southern white paternalism. northern paternalism started to dovetail with the kind of white Southern paternalism that Ryland had practiced for so long as trying to be kind of a cultural conduit for Black southerners to come into the Christian mainstream. And so when white Northerners, who are helping administer the seminary, recognized in Ryland particular expertise in handling, or working with, I mean all the language they use is paternalist, Southern freed people, then that represented, again, not a step towards equality but a kind of convergence of the softer white supremacy of paternalist thinking on the part of both white Northerners and southerners.

KIERNAN: White supremacy and paternalism, as Irons said, certainly did not disappear with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Racism toward Black people persisted in both the North and South. When Ryland died in 1899, lynching was at its all time peak, and Jim Crow Laws had started to appear.

In his last year, Ryland wrote a monograph called “The Colored People” which expressed the ultimate views he had of Black people, thirty-three years after his connection with the First African Baptist Church had ended:

“It is a misconception of the African race, which many Anglo-Saxons cherish, that all negroes are alike. While the whole human family are depraved, and the sameness of condition, surrounding a particular tribe, will impress on it a peculiar type of character, still there is as much individuality — as much variety of intellectual and moral temperament — among the negroes as there is among persons of any other race. I have witnessed as bright examples of godliness, of disinterested kindness, of real gentility of manners, and of native mental shrewdness among them, as among other people.

“The negroes are now all free, and I am heartily glad of it, though I say nothing of the agencies and methods by which the event was accomplished. They are our fellow-men — our fellow-citizens — and many of them our fellow Christians. Let [us] treat them in the spirit of our common Christianity.”

It is unclear exactly where those words signal Ryland left off. It seems he readily accepted and approved of the freedom of formerly enslaved people, and perhaps had developed a slightly less paternalistic attitude toward Black people, although that tension remains even in that final monograph. And he didn’t seem to look kindly upon Reconstruction or the results of the Civil War aside from emancipation. Irons attempts to explain some of this:

IRONS: Not only is it the abstract question of the justice of slaveholding, but that's caught up in his experience as a white southerner with the devastation and loss of the Civil War, and his frustration with defeat at the hands of the Union Army, which did destroy many of the people in places that he loved. I mean it became tangled up together with this question the abstract justice and slavery in his relationships with the men and women to whom he ministered. And this is all pretty complicated.

KIERNAN: It is complicated. In her thesis, Teresa Payne characterizes Ryland as having two attitudes: one of “earthly paternalism" and another of “heavenly equality.”' The first of these attitudes is expressed by his remark: “We all enjoy private opportunities to exert a kindly influence on the colored people. They are in our neighborhoods and often in our houses. With many of them we are well acquainted and know their needs, their modes of thought and life, and the best methods of approaching them.” The other attitude is expressed by his writing here: "Our bodies are diverse in color but our souls, if they have any color, by nature are equally dark and by the blood of the Lamb, may be made equally white."

Ryland seems to contradict himself at times, seems to say one thing then preach another, preach one thing then do another. It’s murky and, while we can parse a lot from his extensive writing, we unfortunately cannot ask him questions ourselves. What we do know is that his positions as founder of UR and pastor of the First African Baptist Church gave him platforms that empowered and publicized his beliefs and actions. Ryland was not an abolitionist, but a slaveholder, and he seemed to support what he saw as a Christian mission enabled by the institution of slavery. But he also seemed to resist some of its injustices within that religious context.

IRONS: That's what Ryland was specializing in, was how to make the best of the truly wicked unjust system. He did push against it. He pushed against the law for literacy. He seems to have bent the rules to allow more agency for his Deacon board. But in the final analysis, he stood solidly right behind a deeply unjust system.

KIERNAN: So what do we do with all this? How do we categorize Ryland’s legacy, and what do we do, what does UR do, to acknowledge it? That part is up to all of us.

Thank you for listening.

This episode of Beneath the Surface was written, narrated and reported by me, Grace Kiernan.

Additional reporting was provided by Jackie Llanos.

The story was edited by Nina Joss.

And our music, as always, was graciously provided by Nathan Burns.

Contact multimedia producer Grace Kiernan at grace.kiernan@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now