The COVID-19 virus has presented many unknowns, but the research conducted by people within the University of Richmond community can offer some insights. Three UR faculty members shared with The Collegian how their studies are applicable to the current pandemic.

Mathematical applications

Mathematics professor Lester Caudill develops mathematical models that simulate infection spread in hospital wards, with a focus on the spread of antibiotic resistance, he said.

“What’s key to my work though is that in my hospital infection models I have, kind of, multiple things going on at once,” he said.

Caudill creates models that can track both external and internal interventions on the body simultaneously, such as disease spread through human interaction and changes in bacteria populations inside the body from drug treatments, he said. His models simulate experiments that cannot be conducted on humans because of health implications and the need for controlled conditions, he said.

Caudill's models could be adapted to measure the effectiveness of COVID-19 interventions, Caudill said. For example, his models could track the efficacy of personal protective equipment, an external intervention, as well as internal interventions such as treatment options.

“If we wanted to look at the effectiveness of face masks, then that would be how individuals, how people interact with one another,” Caudill said. “But a vaccine — or if they actually develop a drug that will treat someone who has an active COVID case already — that would not be about that person interacting with other people. It would be about what’s going on inside that person’s body.”

In summer 2020, Caudill and his student researchers simulated COVID-19 spread in two scenarios: 1) infection spread by asymptomatic virus carriers in a community; and 2) infection spread on a hospital campus, he said.

In spring 2020, Caudill taught a class called Mathematical Models in Biology and Medicine, which he centered around the COVID-19 virus. For the course’s main project, students used models to find answers to some of the questions the public wanted to know about the virus, Caudill said. For example, students researched the consequences of ending stay-at-home orders at different times, and of implementing distancing measures for the entire population versus only at‐risk groups, Caudill said.

Caudill hopes to expand the use of his models to explore the implications of COVID-19 interventions, such as stay-at-home orders, beyond healthcare, he said. Caudill said it troubled him that while he had been able to continue working during the stay-at-home order in Virginia, many other people had lost their jobs.

“I’ve got this idea in my head of trying to develop a model that incorporates ... social factors and economic factors as well as the public health factors,” he said. “[The model would] investigate not only the value versus the price of something like a stay-at-home order, but more generally, maybe, explore possibly more equitable ways of accomplishing that same kind of health protection to the community.”

Pandemic literature

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

English professor Elizabeth Outka is the author of “Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature,” which investigates traces of the 1918-19 influenza pandemic in interwar literature.

Outka has long studied literature from the interwar period, or the time between the two world wars, she said, but it took her a while to identify the flu pandemic’s imprint on the works she has studied.

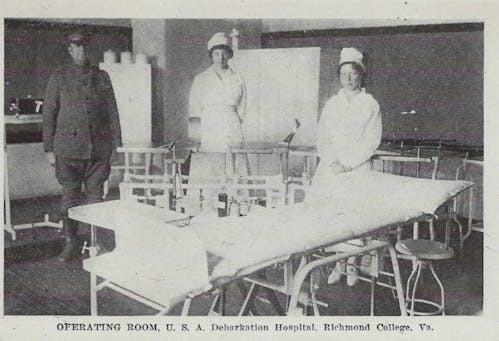

Interior of the temporary hospital set up in North Court for returning World War 1 soldiers and influenza victims.

Courtesy of the Virginia Baptist Historical Society

“In the British texts that I mainly study, the pandemic’s traces are more covert,” she said. “They were written right in the aftermath of the pandemic, when people didn’t really have a framework in which to understand it or know quite what story they were in — similar to the moment we are in now with COVID-19 — where all they had were fragments of the body’s memory and what it was like."

Outka said she had missed the pandemic’s traces even in books she had taught many times in class. Outka chose not to structure her book chronologically so she could more clearly direct readers' attention, she said.

“There’s usually a lag time in art,” Outka said. “We usually need some years before we can write about a traumatic event. And so I start the book with the works that were written toward the end of the interwar period that treat the pandemic directly, where it’s clear they are talking about the influenza pandemic ... And then once we have that in our minds, then we can read these other [earlier] works and be closer to the mindset of the people who were writing at the time.”

Outka hoped this structure would allow readers to read through the lens of the pandemic, she said.

Outka focused on sensory history — understanding the sights, sounds, smells and tastes of the time — because stories of the pandemic were so often fragmented, she said.

For example, she looked at letters collected by historian Richard Collier, who placed ads in major newspapers in the United States and Europe in the 1970s asking people who remembered the influenza pandemic to write to him about their experiences, Outka said.

"[Sensory history] tells us all of these things about the atmosphere and emotions of a particular time period, and these letters were really evocative of those things," she said. “And so you got a real sense of what people were hearing and smelling.

"One thing that goes all the way through are the sounds of bells. Everybody talks about how the bells rang nonstop for the dead in the pandemic, and then suddenly all of these works where there are bells ringing all the time suddenly resonate differently."

Because of the uncertainty that comes with a pandemic, people are often drawn to narratives with identifiable villains and heroes, Outka said her research showed.

A makeshift operating room in North Court during the late 1910s.

Courtesy of the Virginia Baptist Historical Society

“The history of disease is so often a history of discrimination, and we see that with the 1918 pandemic and we’re already seeing that with COVID-19,” she said. “When you’re faced with an invisible enemy, sometimes the desire is to make a visible one and then scapegoat that group or person.”

This is evident in the works of horror writer Howard Phillips Lovecraft, Outka said.

“He creates these proto-zombies that arise out of war and pandemic ... from this miasma of what he felt was this contaminated landscape, because of all of these 'outsiders' and deviants,” she said. “You really feel like you need a shower after you read some of his early work, I have to tell you."

This trend appears outside of the 1918-19 pandemic, too, Outka said.

"I think we’re seeing a lot of that today where we have attacks on a group," she said. “We see this in other pandemics as well. Certainly we saw this in the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

"Pandemics are often excuses to go after a particular marginalized group and say, 'It is this group’s fault.' And it gives a direction to the anger and the fear, with monstrous results.”

Vaccine development

Visiting biology lecturer Michael Harwich has spent his career studying infectious diseases. Harwich taught a class called Emerging Infectious Diseases in spring and fall 2020, during which the classes often discussed the COVID-19 virus, he said.

Harwich has worked on multiple trials for virus, bacteria and cancer vaccine and therapeutic development as a research and development scientist, he said.

There are many tests conducted throughout the vaccine development process, he said. The basic structure of vaccine development involves a pre-clinical phase and three subsequent clinical phases in which the safety and efficacy of a vaccine is tested on people, Harwich said. Also, there are often sub-branches within each phase in which more specific tests are conducted, such as exploring the optimal quantity and frequency of dosages, Harwich said.

The vaccine testing window should be long enough that the developers are confident there will not be secondary symptoms or complications among those vaccinated, Harwich said.

"[The COVID-19 virus is] mainly a respiratory pathogen, but there’s some weird loss of taste and loss of smell," Harwich said. "When you have one agent causing such weird, diverse symptoms, that’s one to me that I feel like you’ve got to look at longer.

"Because when you take a piece of that virus or that agent and use it as a vaccine and you’re injecting those into people, what does that piece do? How does that little piece contribute to these wide-ranging symptoms?”

Harwich's previous vaccine trial work underlines how quickly the COVID-19 vaccine development has occurred, he said. Harwich worked on early trial studies for respiratory diseases and said pre-clinical projects alone usually took at least a year.

“This can take years, and that’s why the SARS[-CoV-2] one that we’re living through is really remarkable," he said. "... What our industry has done and what these companies have been able to achieve is pretty remarkable.”

Features editor William Roberts contributed to reporting.

Contact managing editor Emma Davis at emma.davis@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now