President of the Society for American Music Tammy L. Kernodle gave the 18th annual University of Richmond Neumann Lecture on Music Monday night in the Ukrop Auditorium.

Kernodle is a professor of musicology at Miami University of Ohio. Her scholarship highlights the influence of black women in jazz, classical and popular American music. Her scholarship has generally been concerned with black women musicians of the 20th century, notably Mary Lou Williams.

But in her lecture Monday night, “Cry No More: Black Music and the Mythology of Post Racial America,” Kernodle historicized the role of contemporary black women musicians in shaping the current protest culture of the U.S. in the years since the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012.

“For me, it’s the responses of black women artists that are the most striking,” Kernodle said. “This is because, outside of a few instances, male musicians still are situated as the primary articulators and promoters of resistance culture in America.”

On Monday night, Kernodle played for the audience three different performances: Lauryn Hill’s “Black Rage,” Rhiannon Giddens’ “Cry No More” and Janelle Monáe’s “Hell You Talmbout.”

Historically, black women artists' resistance expressions and anger have been suppressed and censored by radio stations, record labels and the cultural industry for the sake of profit and reputation, Kernodle said.

One example is Alicia Keys' 2014 protest song "We Gotta Pray," which she wrote in response to the police killing of Eric Garner and others. The song was never promoted by her label and wasn't released on her album out of fear that the protest song would harm Keys' reputation and make the album less profitable, Kernodle said.

One way Hill, Giddens and Monáe, among others, have shaped the current resistance culture is by releasing their protest music through sharing platforms like Soundcloud, Youtube and NPR, and refusing to let record labels edit and censor their music, Kernodle said.

Kernodle also discussed how black women musicians have shaped the current resistance culture by disrupting narratives of a post-racial America.

Sociologists and political pundits began to speculate in 2008 that the election of Barack Obama signified the coming of a post-racial America, Kernodle said.

"The blackening of American popular music," coupled with Obama's engagement with artists across genres, his curation of Spotify playlists and concerts at the White House, "all amplified notions of post-racial America collectively joined through musical engagement," Kernodle said.

Kernodle highlighted reality-based music competition shows such as "American Idol" and "America's Got Talent" as exemplifying how white singers have appropriated black female vocality, forwarding post-racial notions through singing.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Notions of post-racial America halted during Obama's second term after an increase of police killings of unarmed black Americans, Kernodle said. The series of violent killings by police officers led to nationwide protests, the formation of resistance groups such as Black Lives Matter and calls to action by artists and activists in the hip hop community.

In response to the shooting of Michael Brown by police in 2014, Hill released the song “Black Rage” on Soundcloud in August 2014. The song’s lyrical arrangement is based on Richard Rodgers’ song “My Favorite Things” from the movie “The Sound of Music.”

“Hill subverts a song centered on the pleasurable experiences that helped one young woman buffer against the hurts of the world into a historical narrative outlining the exploitation and brutalization of black bodies,” Kernodle said.

In “Black Rage,” Hill engages with “sonic code switching,” which Kernodle described as the use of white popular music conventions to obscure black female anger in order to capture white listeners. One early example of sonic code switching is the lush instrumental and ornate lyrics of Billie Holiday's original recording of “Strange Fruit,” Kernodle said.

In the aftermath of the 2015 massacre of nine African Americans at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, by a white supremacist, Giddens released the song “Cry No More” through NPR music on July 15, 2015. Like Hill's music, “Cry No More” places the Charleston massacre into the historical narrative of terrorism against black Americans.

Kernodle equated Monáe's August 2015 song “Hell You Talmbout” to Nina Simone’s 1964 song “Mississippi Goddam.”

"[Hell You Talmbout] aligns itself with the communal aspects of the types of resistance singing that framed the intersection of the direct action campaigns and non-violent resistance music of the 1960s," Kernodle said.

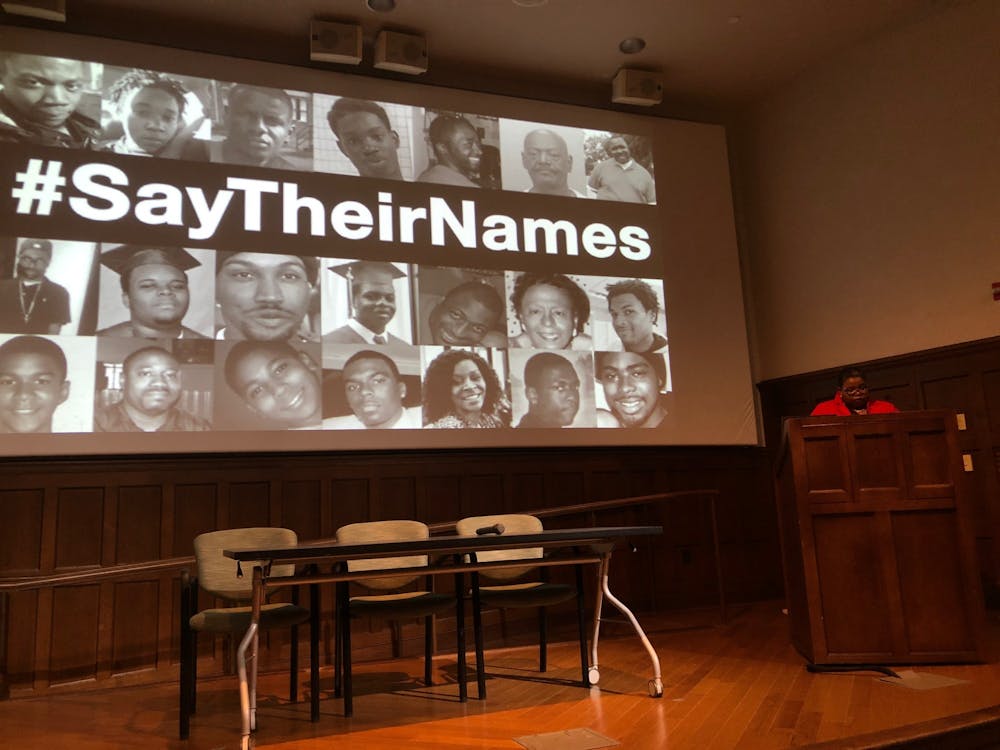

The verses of "Hell You Talmbout" list the names of 16 black Americans — including Sandra Bland, Eric Garner and Walter Scott — who were killed by police in the last two years of the Obama presidency. The song also names Martin and Emmett Till.

One event that led Kernodle to examine the roles of contemporary black women musicians in current resistance culture was when she had been stopped by police while driving home from church one day.

The first question the officer asked her was whether she owned the car. Then, for more than 45 minutes, three police officers berated her with questions, seemingly trying to convince her that she didn’t own her car, she said.

“Much like Sandra Bland, I had a real attitude,” Kernodle said.

Contact features writer William Roberts at william.roberts@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now