A burial ground of enslaved people is believed to be beneath the University of Richmond. The burial ground is behind Puryear Hall, near the steam plant and parking lot U8, according to documentary evidence uncovered by a graduate student.

“Right before the University of Richmond got this land, part of this area was a park, designed by The Olmsted Company,” said Dywana Saunders, research and digitization associate for Boatwright Memorial Library. “But before 1865, it was a plantation owned by Benjamin Green.”

Saunders initially began her research for the Gambles Mill Project in 2016. She collected all the historical documents she could find, such as maps, articles and primary documents, she said. In doing so, Saunders said she had started learning of the land’s history and had begun to find references to Green’s plantation as well as burial grounds on it.

“At the time, the Westhampton side of the lake and just a small sliver [of land], which was actually the burial ground, was owned by The Grand Fountain of the True Reformers,” Saunders said. “It was an African-American organization, who was exploring the possibility of using this land as a retirement center for the African-American community.”

Shelby Driskill, a UR graduate student pursuing a masters in liberal arts, uncovered the corporate connection of the hiring of the of The Olmsted Company, which led to the discovery of a report by H.V. Hubbard, written on Jan. 14, 1902, for The Olmsted Company.

Hubbard’s report defined what section of this land was owned by the True Reformers and what section was part of the park. Saunders found that Hubbard’s report also aligns with the history of UR’s property before it was owned by UR.

In his report, Hubbard writes, “the land of the True Reformers runs in a little triangle into the property of the park, passing just back of the present spillway, including a negro burying ground, and returning along the line of the old road down the hill just to the east of the burying ground.”

An excerpt from the microfilm version of H.V. Hubbard's report, which details a "negro burying ground" on the University of Richmond's present-day campus. Edited by The Collegian staff to show the most relevant portion. Source: The Olmsted Company's project notes by H.V. Hubbard, January 14, 1902, Westhampton Park Project (#00100), p. 2, Library of Congress, Box B14 Reel 11

Saunders believes that the “present spillway” Hubbard wrote about is regarding the dam of today’s lake.

A current map of the University of Richmond's campus, edited by The Collegian to show the approximate location of the burial ground of enslaved people. Source: University of Richmond virtual tour

Other documents also suggest that the burial site is behind what is now Puryear Hall.

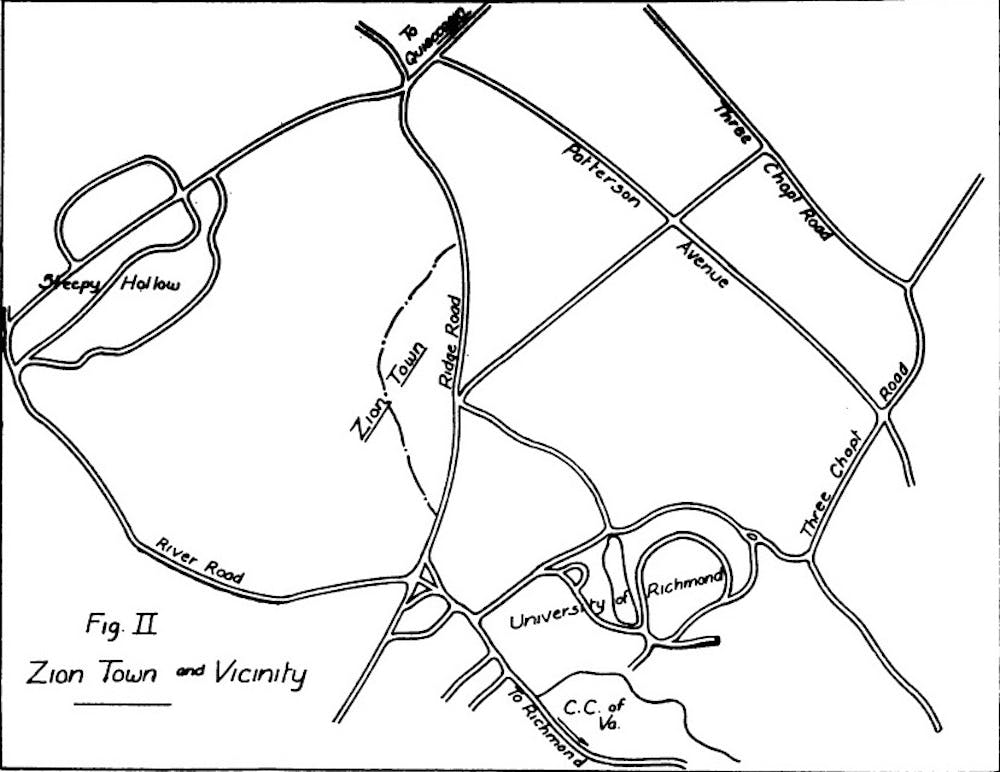

The Grand Fountain of the True Reformers was within close proximity to Zion Town, a historically African-American community close to UR’s land and near what is currently the Kuba Kuba Dos restaurant, Saunders said. Within the former Zion Town neighborhood, Ziontown Road still exists today.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

A map of a Zion Town, a historically African-American community close to UR’s land and near what is currently the Kuba Kuba Dos restaurant. Source: “Ziontown: A Study in Human Ecology” by H.H. Harlan, 1935

It is through a Zion Town oral history that Saunders found documentation about the burial ground on UR’s campus. The publication, “Ziontown: A Study in Human Ecology,” by H.H. Harlan, was published in 1935.

Additionally, the oral history verified that the burial ground is that of enslaved people from Green’s plantation.

“Westhampton Lake, in the center of University campus, was [Green’s] millpond, and the dam marks the site of his mill,” Harlan wrote. “Some few years ago a gang of laborers digging in the hollow just below this dam uncovered a pile of bones and skulls that are considered to mark the site of the old burying ground for Ben Green’s slaves.”

An Oct. 1947 Richmond News Leader article wrote that people on UR’s campus had also encountered such burials in the earlier half of the 20th century.

“A small pile of bones, believed to be the skeletons of slaves buried more than 100 years ago, were un-earthed at about noon today by a crew of workmen on the University of Richmond campus,” the article reads. “The workmen who made the discovery were engaged in the widening of the road which borders the university lake and the Richmond College campus.”

The article states that the bodies uncovered were the remains of two people and were reinterred a few hundred feet away.

On Nov. 7, 1947, a Collegian article details the same discovery.

A verbal history with Ed Boynton, an engineer in charge of the Wiley Wilson office in Richmond, also indicates that people have encountered burial sites. Wiley Wilson is a full-service architectural and engineering firm. Boynton took part in the 1949 construction of steam tunnels between Richmond Hall and the steam plant.

“When we were digging the tunnel from the power plant toward Richmond Hall, we uncovered a series of unmarked graves,” Boynton said in the verbal history. “In fact, it stopped the work and the University arranged to have the bodies buried someplace else.”

The location of the bodies, discovered during the widening of what is now Richmond Way and the construction of the steam plant, remains unknown. It is also unclear whether bodies from both instances were moved to another location on UR’s campus or off campus.

Sightings of unmarked and unknown slave burial grounds are common in the U.S., said Derek Miller, assistant director of community relationships and community-engaged learning at the Bonner Center for Civic Engagement.

“People say, ‘Wouldn’t the families be there to recognize, maintain, protect this sacred space?’” Miller said. “We’re talking about the context of enslavement. You could be sold the next day to someone else. The varying network of those connected to [the burial ground] could become dispersed very quickly.”

It is unknown when the burial ground was created and when people stopped being buried there.

“We have records that suggest that it was there during the plantation period, this is why we can say it was an enslaved burial ground,” Miller said. “Does it get stopped when the plantation ends and when slavery ends in 1865? Maybe, maybe not.”

Miller has worked as an archeological consultant for UR regarding the burial ground and advised UR to hire NAEVA Geophysics, Inc. to do a ground-penetrating radar survey on the supposed burial site.

This survey will be conducted in September, Miller said. Ground-penetrating radar is a non-invasive technique that could possibly show the burials and confirm whether they are present.

Ground-penetrating radar is most effective in soils closer to tide water. Areas such as UR tend to have more mixed results because of the more clay-like soils in this region, Miller said.

“One of the things archeologists often talk about is whether the absence of evidence is in fact evidence of absence,” Miller said. “In terms of the ground-penetrating radar, it has a possibility to show us surviving burial grounds. But if it doesn’t, we can’t take that as proof that there aren’t burials there.”

The documentation of this burial ground is a reminder of how UR’s landscape is built upon enslavement, Miller said.

“Who built the lake? It is a man-made lake. The landscape we are on is constructed by slave labor,” he said. “[This campus] is in fact a plantation landscape, even if we don’t view it as that now, even though the university never [owned] a plantation here.

“You can’t go anywhere and not be impacted by the landscape of enslavement in the same way you can’t walk and be a part of the American culture and not be impacted by the legacies of enslavement. And, you can’t look at that lake, or at least, I can’t, once you know the fact of why that lake even exists, who is responsible and what is the institution that made this possible.”

Miller said he was impressed with UR’s response to this evidence and the facility department’s efforts to be respectful of the area.

“When we presented this evidence to facilities, they immediately said ‘Let’s not do anything,’” Miller said. “They have me on speed dial in case the steam tunnel explodes because they will have to address the utilities that exist there if possible and do that as responsibly as possible. Our facilities are doing everything in tandem to do the best they can to preserve what is there now.”

Although there is documentary evidence suggesting that this burial ground exists, Miller said that it could not yet be fully confirmed.

“If we want to get real specific as to who these people are, we have to dig,” Miller said. “But, we have a thing about the moral and ethics of this, not from an archeological perspective, but from a human perspective. That means we are disturbing the dead. That’s not our decision to make. That should be the descendant-community’s decision.”

A UR committee plans to research to determine the location of the burial site for enslaved people who lived and worked on the land where UR is now located and create a plan for memorialization in 2020, according to the report, Making Excellence Inclusive: University Report and Recommendations, released on July 8 by University President Ronald A. Crutcher.

By 2022, the committee aims to connect with the descendant community and support ongoing work to integrate historical context into campus, according to the report.

The committee for this burial site will be run by UR’s executive vice president and chief operating officer, David B. Hale, and UR’s interim senior administrative officer, Amy Howard.

Howard will serve as the interim senior administrative officer for the next 12 to 18 months, according to an email Crutcher sent to the university community on July 11.

In a New York Times opinion article on July 16, Crutcher wrote that the commission on history and identity was aimed to ensure that UR probes the depths of its history in terms of racial understanding.

“We’re enlisting a public historian to coordinate with faculty and students to help us tell a fuller, more inclusive story of who we were, are, and aspire to be,” Crutcher wrote. “Work that includes memorializing figures such as the enslaved people who are believed to be buried on our campus and the first black alumni of Richmond’s undergraduate program.”

Driskill, who found Hubbard's report, has done extensive research seeking available evidence of the burial ground. She has researched biographical glimpses of the lives of those who were enslaved on the property and enslaved elsewhere by the property owners, she wrote in an email.

Through Driskill’s research, she has found “contemporary news accounts, auction information, letters, advertisements, insurance documents, wills, and property transfers,” she wrote.

“I have collected the evidence connected to the site, and biographical details of those enslaved by the property owners,” Driskill wrote.

Driskill’s digital narrative, “Paths to the Burying Ground: Enslavement, Erasure and Memory on the Campus of the University of Richmond,” is a project that was constructed under the auspices of two UR courses and a period of personal research to show her findings.

The digital narrative will be publicly available for viewing and consideration around mid-August, Driskill said.

Contact international editor Olivia Diaz at olivia.diaz@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now