With its nightlife, niche microbrew scene, museums and top-notch institutes of higher education (you may even attend one such school), it is likely that many people would say Richmond is a cool city.

But according to the findings of a team of researchers from around the local area and elsewhere, Richmond is not very cool. In fact, with heat-trapping gases building up in the atmosphere, the city is alarmingly and dangerously hot, and it is warming up much more quickly than its neighbors. Even on a planet that is getting hotter and hotter all over its surface, the city of Richmond stands out.

One of the scientists from that research team, Jeremy Hoffman, explained this to a group of University of Richmond students at a talk on April 10 as part of Earth Week, a series of events sponsored by Green UR meant to spark conversations about the relationship between business and sustainability.

Hoffman works at the Science Museum of Virginia, where he is a climatologist and earth scientist, and he is also a faculty member of the Center for Environmental Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University. He regularly gives talks to groups about the far-reaching effects of climate change, according to his website.

Hoffman’s talk in the Brown-Alley Room of Weinstein Hall focused on city planning, and how different areas of cities like Richmond can be drastically hotter or cooler than each other, even when those temperatures are recorded at precisely the same time of the day.

“You might not think about it, but cities are businesses,” Hoffman said. “Everything about the inside of a city and the way that a city works is related. It’s an ecosystem of its own accord, and it does a lot of things that only 30 or 40 years ago we didn’t know a lot about.”

With his background in earth science and position at the museum, Hoffman said he thought it would be prudent to learn more about heat waves and how they impact cities.

A few years ago, along with several partners including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Virginia Academy of Science and Todd Lookingbill, a professor of biology and geography at UR, Hoffman established the Richmond Urban Heat Island Collective.

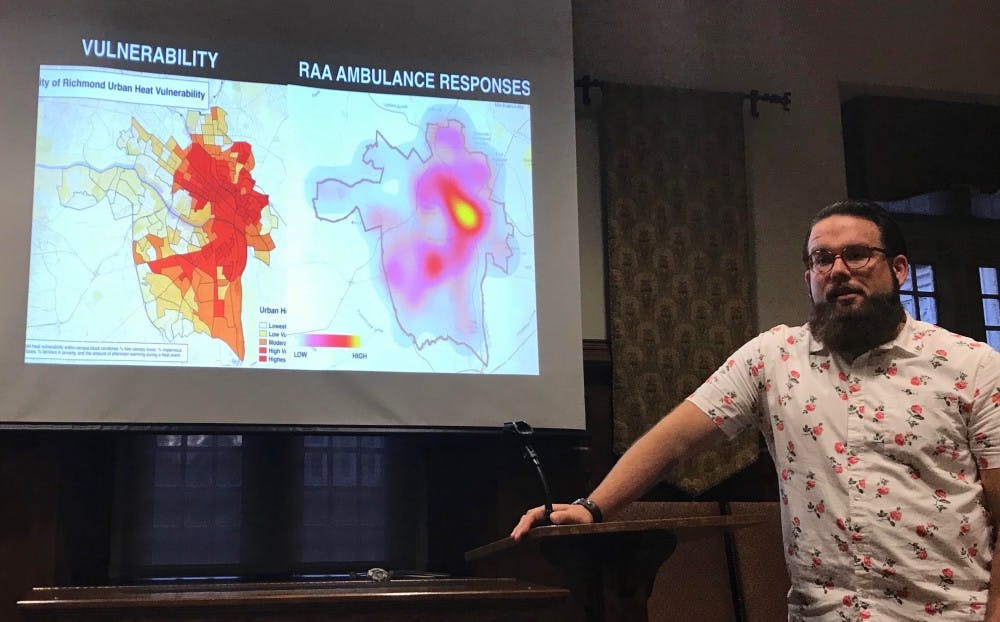

This group is dedicated to studying the “heat island effect” in Richmond — that is, investigating those parts of the city that are disproportionately hot and determining why they are like that and how the effect can be mitigated.

As part of their research, Hoffman and other members of the collective would attach heat sensors to vehicles and take frequent drives around the city in order to record the temperatures of different neighborhoods and areas, such as the Museum District, the Fan and Scott’s Addition.

“We had to go out at 6 a.m., very early in the morning; 3 p.m., the hottest part of the day; and 7 p.m., the time of the time of night when it starts to cool down,” Hoffman said. “I saw a 16-degree difference between the warmest and coolest places at the exact same time. That’s huge.”

He presented a graph displaying some of the collective’s data, which indicated a strong correlation between a neighborhood’s heat and its social and economic demographics.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Areas with overall cooler temperatures at all times during the day tended to be populated by people who are white, have college degrees, drive to work and own their homes. Hotter neighborhoods, by contrast, tended to be mostly populated by people of color who rent their homes and take public transit to work.

“Poverty also had a role to play in what areas were hotter,” Hoffman said. “So if you think about vulnerability to heat, it might be related to your ability to buy a fan. If you don’t have a lot of money and you have to keep your refrigerator on or turn on the air conditioning, what kind of decisions are you going to make? In some of these areas that are very high poverty, you can’t actually put an air conditioning system in your structure.”

The issue can only be solved by redesigning certain parts of the city and by building housing that would be affordable to people with lower incomes in cooler areas. Both avenues have had little success, however.

Government officials have so far paid little attention to the Richmond Urban Heat Island Collective’s findings, Hoffman said. Further, residents and businesses of affluent areas generally oppose the construction of affordable housing in their neighborhoods — a phenomenon known as “Not In My Backyard."

Still, Hoffman is confident of the city’s ability to combat the expansion of heat islands and other effects of climate change, and believes it is important for college students to take what they learn and apply it in order to save the planet, he said.

“By the mid-part of the century, we might have as many as 40 to 50 more days above 95 degrees in this area due to the change in climate,” Hoffman said. “That’s assuming that we just continue to burn the fossil fuels as we have. So this is entirely controllable and up to us to decide that that’s not the case.”

Sophomore Will Walker, a student who attended the talk, said he appreciated the fact that he was able to learn so much about a topic he was unfamiliar with.

“Honestly, I was surprised by the connection between poverty, blackness and the heat,” Walker said. “Also how detrimental climate change is for these communities. I had not thought about the correlation between climate change and living in those communities before.”

Sophomore Mitchell Gregory said that he, too, enjoyed the presentation. Hoffman’s information about heat islands made him think of other threats caused by climate change that compromise cities, such as sea level rise.

“I was on the SEEDS Louisiana trip and that stoked my interest a lot in how these low-lying areas are vulnerable to climate change,” Gregory said. “That’s something that we see in Norfolk, which is much closer to home.”

Throughout his presentation, Hoffman reiterated several times that the responsibility for solving the heat island issue in Richmond and cities like it lay in the hands of the people.

“There are ways to make housing less expensive,” Hoffman said. “There are ways to increase the density of areas. But it requires us to have difficult conversations about not only what we want the city to look like but the type of experience that we have in the city.”

Contact contributor Hunter Moyler at hunter.moyler@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now