Editor's note: This story contains a graphic description of violence.

Disappointment. Anger. Disgust.

These were the emotions that black students Dominique Harrington, Kidest Gebre and William Walker felt when they first saw the 1980 photo of black alumnus Michael Kizzie, '81, smiling brightly surrounded by students in Ku Klux Klan costumes — a drink in his hand with a noose around his neck.

The photo was captioned “Kizzie ‘hangs’ around lodge.”

“Today, we still have to [have] simple conversations about racism,” Harrington, senior, said. “I shouldn’t have to explain to people why blackface is bad. I shouldn’t have to explain to people why wearing Klan outfits is bad. It was 1980 and there were students of color on this campus and people were acting this way. This is unacceptable.”

To black students, the noose and the KKK are symbols of historical violence and oppression -- past atrocities that largely went without due justice, and are largely ignored by those who are not black.

After the photo circulated on social media, President Ronald A. Crutcher sent an email out on Feb. 7 to the campus community condemning the photo.

“The image that was shared from the yearbook is repulsive to us,” Crutcher wrote in the email. “Images of this sort, and the behavior and attitudes they represent, are appalling and antithetical to the values of the University today.”

Walker, a sophomore, said he had found the president’s email reassuring, but pointed to what he thought was a larger problem — non-black students who did not understand the problematic context of the photo.

“There were people in the dining hall who were talking about it and said something on the lines of ‘It shouldn’t have been a problem because the black guy in the picture was smiling,’” Walker said. “I don’t know how much reaffirming a college can do if it’s not working toward changing the culture of the students here on campus.”

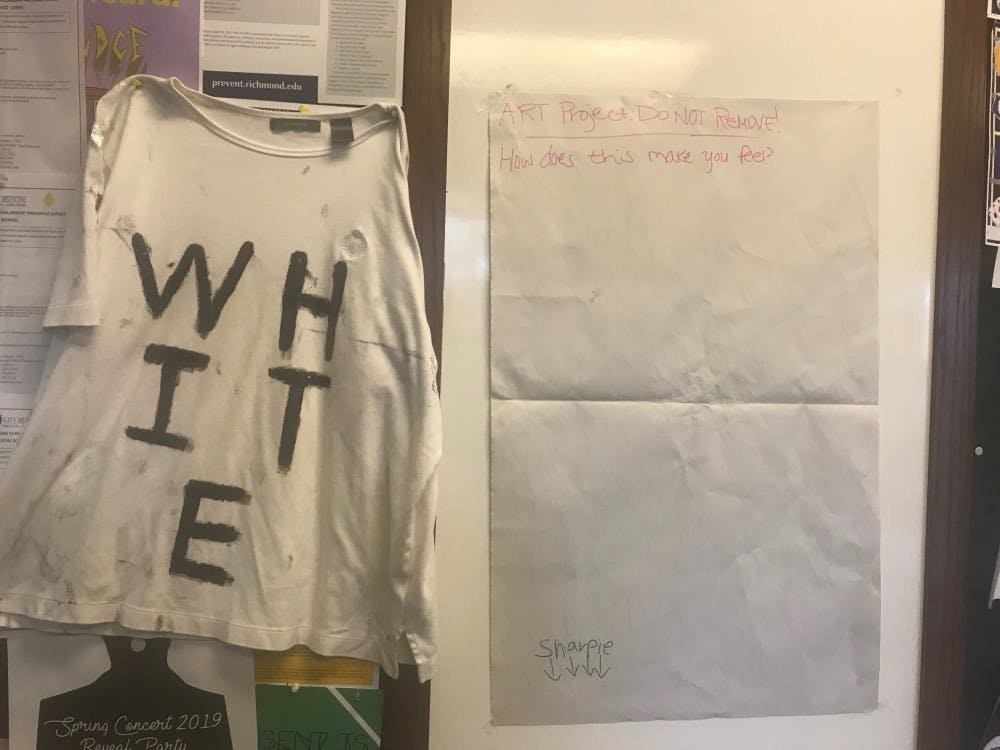

Gebre, a junior, was working on an art project for her "Visual Media Arts Practice: Site and Subjugation" class when she first saw the photo. Her art project involved using white shirts as canvases for political discourse. Although she had originally planned to write phrases such as “black is beautiful,” the photo sparked a new idea.

“I knew there wasn’t going to be any political engagement from the students on campus,” Gebre said. “That’s what got me mad, so I decided to write two words, 'black' and 'white.'”

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

The shirts were styled to look dirty and ripped. She placed them at different spots on campus, each with a marker and paper next to them that asked, “How does this make you feel?”

On the shirt with “white,” a person responded that it had startled them, but that they appreciated the project. What took Gebre by surprise, however, was a response on the shirt with “black,” where someone wrote that the shirt would incite a negative response.

“How does the word black written on a T-shirt incite a negative response?” Gebre said. “Whoever wrote that, their idea of political engagement went automatically to violence.”

From 1882 to 1968, lynching of blacks -- typically by hanging -- was at its height. Experts have documented an estimated 4,700 lynchings. The majority of the victims were black. White people used lynchings to instill fear into black communities and re-establish racial hierarchies lost after the Civil War.

Often treated as a source of entertainment for white townsfolk, lynchings were extremely brutal.

According to an NAACP article, one victim, Mary Turner, was hung by her ankles, doused in kerosene and lit on fire. While she was still alive, a member of the mob slit open her stomach and her unborn baby fell to the ground and was promptly crushed by the mob.

“It’s terrorism,” Harrington said. “My mom’s side of my family was driven out of their hometown. My family member had to dress up like a woman to escape Klansmen who had threatened to lynch him. All of my grandparents have passed by folks who have been lynched.”

Although lynching is often associated with the past, it is still a reality for black Americans.

In 2017, a group of teens taunted an 8-year-old black boy with racial slurs and threw rocks and sticks at him, according to the Washington Post. The teens and the boy ended up on a picnic table where the teens grabbed a rope from a tire swing, tied it around the boy’s neck and pushed him off the table. The boy narrowly survived the attack.

On Jan. 29, two men attacked actor Jussie Smollett while yelling racial and homophobic slurs. He told police they threw chemicals on him and tied a rope around his neck before fleeing. Smollett was hospitalized, but survived the attack with non-life threatening injuries.

Lynching is transcendent of time, Harrington said.

“It still has that same meaning that it did back then," she said. "It’s traumatic and that trauma is passed down.”

Contact news writer Joshua Kim at joshua.kim@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now