Editor's note: Today, The Collegian is introducing columns from contributors to its coverage. This story is the first of a column focusing on sustainability, written by an intern for the Office for Sustainability.

This year, the University of Richmond continued to expand its “Rethink Waste” campaign, as part of the university’s commitment to diverting 75 percent of waste from the landfill by 2025.

The campaign was marked by a campus-wide rollout of standardized waste separation bins, equipped with infographics to aid students with proper waste separation and color-coded disposal bags. Such improvements were implemented to help ensure recycling and waste materials end up at the correct post-consumer destinations.

But despite the opportunities offered by UR to divert campus waste to recycling or reuse, challenges still exist. Recent waste audit data shows that a significant proportion of recyclable material is still being sent to the landfill, largely because of improper student waste separation and contamination.

Richmond’s Waste System

The university’s sole waste operator is Waste Management, which is responsible for collecting waste and recycling materials from the university and delivering them to their proper destinations.

The majority of our municipal solid waste is transported to the Old Dominion Landfill, located 12 miles away in Henrico County. Anything thrown into a landfill bin, including misplaced recyclables, will be brought to this landfill without sorting.

Single-stream recyclables -- the uncontaminated mix of papers, plastics and other recyclable materials placed in the blue recycling bins on campus -- are sent to the County Waste Material Recycling facility about 18 miles away.

The university also recycles cardboard and metal and composts yard waste, each of which is sent to a handling facility in the surrounding Richmond area -- Weyerhaeuser Industries, Sims Metal Management and Gillies Creek Recycling, respectively.

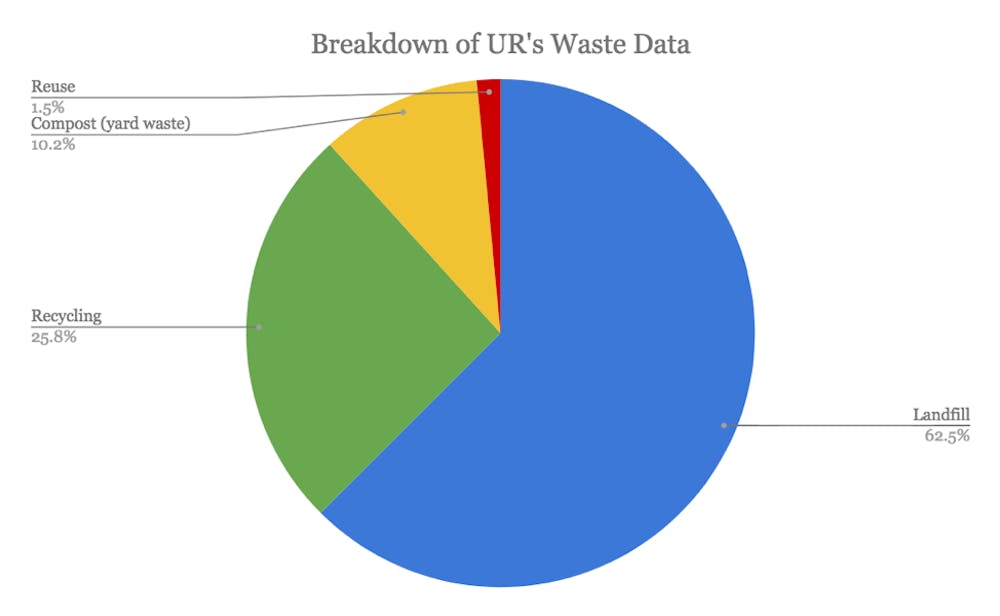

Despite the fact that various waste and recycling facilities exist to capture UR’s trash, improper disposal practices on the consumer side are preventing the university from achieving its waste diversion goal. Current data shows that as of September, the university recycles only 25.8 percent of its waste. Instead, 62.5 percent of our waste, or 1,724,131 pounds of trash, is sent directly to Old Dominion Landfill without sorting.

When accounting for composting and reuse, UR in total diverts 37.5 percent of its waste.

Among schools well-known for their sustainability and waste programs, UR has a lot of room for improvement.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

In 2014, Cornell University had already achieved a 76 percent waste diversion rate because of its progressive recycling and compost practices. In 2017, Middlebury College in Vermont achieved a waste diversion rate of 68.1 percent; in the same year, Stanford University reached 63 percent.

However, compared to other schools in Virginia, UR’s numbers are relatively high. In 2016, Virginia Commonwealth University and the College of William & Mary diverted around 32.6 and 38 percent of their waste, respectively. Virginia Tech had a diversion rate of about 39 percent in 2017, excluding compost.

Current Challenges

Although it performs similarly to other colleges and universities in the Virginia area, UR has the capacity to improve its waste diversion rate. So what, exactly, is holding UR back?

From the student perspective, several factors contribute to improper waste disposal. Students comment that taking the time to interpret infographics on waste bins to determine what is recyclable is difficult when rushing to get to class, work or other commitments.

“I try to recycle when I can, but I probably don’t always do it right because it’s not always convenient to separate everything properly," sophomore Emily Lombardi said. "Recycling comes at the cost of convenience.”

Other students have similar opinions, like sophomore Kayra Isyar.

“I don’t always know where to put the materials," Isyar said. “The blue bins are not working because I see food in them all of the time. Why should I separate materials if the bin is already contaminated?”

Further concerns include whether or not materials in the recycling bins are actually sent to a recycling facility. And for many students, recycling simply does not cross their mind when they are going about daily activities on campus.

But although these are all legitimate concerns of students operating in a busy campus environment, improper separation practices on the individual level contribute to larger waste separation challenges.

A major issue holding UR back is contamination. At Richmond, any materials that are deemed unrecyclable, like soft-plastic, compostable materials and food waste, are considered contamination. Other contaminants are liquids, ice cubes and Styrofoam.

On Nov. 15, America Recycles Day, the university held a waste audit on material disposed of in Boatwright Memorial Library, to further understand the nature of waste separation and disposal. According to the data, landfill bins in the library contained approximately 17 percent recyclable materials. Furthermore, 26 percent of material placed in the recycling bins was non-recyclable.

Although many believe having waste materials in recycling bins does not prevent recyclables from being properly handled, for UR, it does. Any contaminated materials sent to the County Waste Material recycling facility incur a fee for UR.

And as a rule of thumb, any recycling bin on campus over 10 percent contaminated is deemed non-recyclable. This means that small contaminating materials like straws, ice or food scraps can add up and cause large amounts of recyclable material to be sent to the landfill.

From the custodial perspective, this is often cited as one of the biggest challenges. To avoid charges for improper disposal practices, custodial services often err on the safe side when judging whether or not a recycling bin is contaminated.

However, although improper separation and contamination still stand in the way of UR’s waste diversion goals, there are students asking for more. Members of the student body have suggested composting, soft-plastic recycling and banning plastic straws as additional measures for sustainable waste practices. But it may be unrealistic to introduce more waste disposal options until UR can master more rudimentary recycling practices.

Bigger Picture

Although UR’s recycling dilemma may not seem like a big deal, it is part of a country-wide, and global, problem. The U.S. is consistently ranked first in waste generated per capita among all other Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that the U.S. generated 262.4 million tons of waste in 2015. Although around 33 million of these tons were combusted for energy recovery, the rest were sent to landfills.

This excess of trash also warms our climate. In the U.S., landfills are the third largest source of methane, a greenhouse gas that is 34 times stronger than carbon dioxide when compared over a 100-year period. In 2017, municipal waste landfills in the U.S. contributed to 95.2 million metric tons of methane gas emissions.

With the recent release of the 2018 IPCC Climate Change report and federal National Climate Assessment, it is clear that waste generation is an important factor to consider in the greater context of current global warming challenges.

The World Bank estimates that by 2025, global municipal solid waste levels will double. It is increasingly important that countries learn not only to reduce waste but also how to recycle properly.

And although waste management and recycling facilities should continue to do their part in handling post-consumer waste, the process of waste reduction and diversion begins at the individual level. The campus community at UR has an important role to play in tackling the challenges of recycling and waste separation on campus.

As a practical rule of thumb, the following materials can be recycled at UR: aluminum, steel and tin cans, empty glass bottles, empty plastics numbers one through seven (Styrofoam not included), all mixed-paper, cardboard and food cartons and tin and bi-metallic containers (such as aerosol cans).

Contact sustainability intern Rylin McGee at rylin.mcgee@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now