Editor’s note: Some of the names in this article have been changed to protect students’ identities.

Emma is her high school's valedictorian, a varsity soccer player, an employee of a local restaurant, a member of the Young Adult Police Commission, a summer intern at a local non-profit, a soon-to-be associate's degree-holder from a local community college and an aspiring lawyer.

She is also a DACA student.

Emma, 17, was just one of thousands of students who applied to the University of Richmond for the 2018-2019 school year. She had worked hard all her life and dreamt of being a Spider. But in January, amidst a stream of admission letters to each of the other schools she applied to, she received a confusing rejection letter from UR.

At UR, undocumented and DACA applicants compete in the international pool, which is need-aware, rather than the domestic pool, which is need-blind. UR has a separate and limited financial-aid budget for international students, Director of Admissions Gil Villanueva said.

“Being need-aware, we will ask the students … once we get to that point where we don’t have resources we’ll ask them to extend a Financial Certification Form, and once we don’t have any money left, we’re need-aware, and once we’re need-aware, we can’t admit you, because we don’t have the resources,” he said. “That happens.”

For UR sophomore Miranda Barbosa, the implications of this admissions policy became clear when she applied to UR in 2016 at the same time as her friend Hannah, 20, a DACA student who also considered UR one of her top schools but was rejected.

“She was, in my opinion, a much more qualified applicant,” Barbosa said. “She was really strong in every way, but obviously she was not documented.”

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, commonly known as DACA, is a program created under former President Barack Obama in 2012 that grants documentation to immigrant children brought to the U.S. before their 16th birthday. Undocumented students must apply for the program and then renew it every two years to maintain their protected status.

As of Sept. 4, 2017, there were approximately 690,000 DACA recipients in the U.S., according to U.S. Customs and Immigration Services. 94.9 percent are from Mexico, Central or South America or the Caribbean.

Jessica Wright, a Richmond native who graduated from UR’s law school last year and currently works for a Richmond-based immigration law firm, explained some of the misconceptions surrounding DACA.

“A lot of people think that it’s a legal status like having a green card or something, but it’s not,” she said. “It’s more so stopping someone from accruing unlawful presence in the U.S., so sort of an in-between between being undocumented and having a legal status.”

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

DACA status applies only to a certain population of immigrant youth. To qualify, a person must have been living in the U.S. before June 2007, Wright said. Those granted DACA status can continue to renew indefinitely, so there is no age-out provision, but the renewal process is costly, she said.

“It’s about $600 just to pay the government, never mind paying the attorney’s fees for it,” Wright said. “It’s not easy to maintain, it’s not a given and it’s very expensive.”

Although DACA status provides children with temporary protection and certain limited benefits, it is not a pathway to citizenship, Wright said.

“It gives them a work permit and in most states it gives them the right to have a driver’s license,” she said. “Since you have a work permit, you have a Social Security number.”

Laura, 17, a DACA student from a local high school, expressed gratitude for the program when comparing herself with her undocumented friends.

“Some of my friends, they didn’t apply for DACA, and right now they don’t have licenses or they can’t work,” she said. “I feel like I’m lucky to have that because I can have a license and I am allowed to work here.”

Wright said that since President Trump repealed the DACA program in the fall of last year, it is no longer accepting new applicants, but current DACA-status holders can still renew their status.

Barbosa considers her friend Hannah’s DACA status as a barrier to equal access to education.

In reference to a competitive college-prep program in their city, Barbosa said she hadn't been accepted to the program, but Hannah had been.

“She was ranked higher than me in our class,” Barbosa said. “We applied [to Richmond] at the same time and I got in, and she got this letter.”

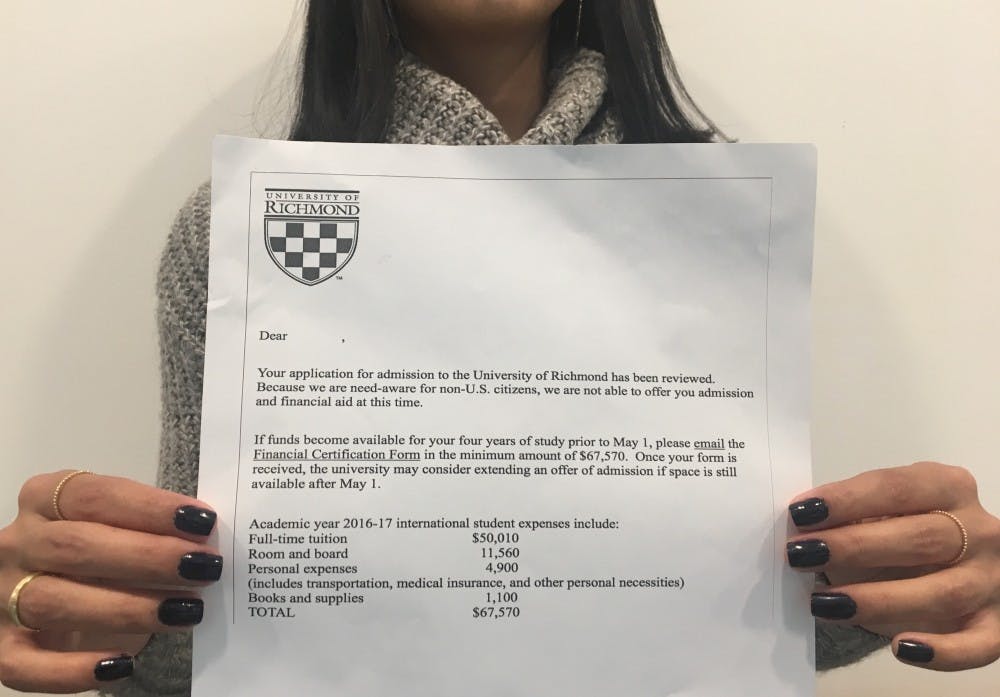

The rejection letter sent to Hannah from UR, which Barbosa deemed as “rude” and “hurtful,” read:

“Because we are need-aware for non-U.S. citizens, we are not able to offer you admission and financial aid at this time. If funds become available for your four years of study prior to May 1, please email the Financial Certification Form in the minimum amount of $67,570. Once your form is received, the university may consider extending an offer of admission if space is still available after May 1.”

In a written statement to The Collegian, Hannah said she had known receiving financial aid would be challenging because she is ineligible for federal funding, but she expressed frustration at the “insensitive” letter.

“In addition to knowing my status, the university was aware that I was a first-generation college student with significant financial need,” the statement reads. “To my family and I, it seemed ridiculous that the university mentioned I could still be offered a position in the Class of 2020 if I somehow, within weeks, came across an amount of money greater than my yearly family income.”

Barbosa said she had also been upset by the response her friend received.

“She didn’t really get rejected,” she said. “They wanted her but they didn’t want her enough to pay for her.”

Laura saw a similar dichotomy when she applied to college.

“It kind of sucks because you’re growing up with all these students that you think you’re equal to, you’re doing the same things they are, but once you get to high school and you’re starting to apply to all these places, they’re getting admitted to all these different types of schools and you’re just like, ‘what am I gonna do?’” Laura said. “[Be]cause I can’t pay for school and I can’t get financial aid as they can.”

After a mentor of Hannah’s wrote to UR expressing displeasure with the letter she received, the university wrote her an apology and agreed to work toward changing the letter’s content.

“We have modified the letter a bit to be more sensitive,” Villanueva said.

But members of the UR community said they thought the changes that needed to be made extended far beyond the letter and into the admission policy itself.

A group of professors belonging to the 2016-2017 Latin American and Latino Politics and Culture Faculty Learning Community issued a statement last year that acknowledged the strides UR has taken to improve accessibility and diversity at UR but cited the need for further reforms.

“Despite these exemplary efforts, our campus continues to lack a representative population of Latino and Latin American students to mirror the students in Virginia’s K-12 educational system: Now 12% Latino and Latin American. Current UR students thus lack exposure to the promise and potential of all their millennial peers,” the statement reads.

The statement ultimately called for policy change to combat the exclusion of DACA students.

“We should provide them with the same opportunity we do our domestic applicants: Need blind admission, the meeting of 100% demonstrated need,” the letter reads.

Wright agreed that DACA students should be included in the domestic pool.

“It’s amazing that they pool them in with international students, because they do have a Social Security number here, they’re authorized to work in the U.S.,” she said. “They’re not here unlawfully anymore. That’s nuts.”

Barbosa echoed these sentiments, adding that her friend Hannah is now doing well at a different institution.

“She’s lumped in with them even though this is her home country, she’s never known another country,” she said of Hannah being put in the international pool, which she said she believed had resulted in her rejection from UR. “Now she goes to a liberal arts school that’s comparable to Richmond … They’ve been so supportive, so she’s better off there than she would’ve been here.”

The school Hannah attends is one of a growing number of highly competitive liberal arts institutions across the country that have adopted more open admissions policies toward undocumented students in recent years. Unlike UR, these schools consider DACA students as domestic applicants, are need-blind and meet 100 percent of demonstrated financial need of those admitted students.

These include Tufts University, Oberlin College, Rice University, Wesleyan University, Swarthmore College and Bates College. Additionally, schools such as Franklin & Marshall College — which considers undocumented students eligible for the same aid as any U.S. citizen — and Georgetown University — which is need-blind for all applicants — have recently taken a more progressive stance.

But there was a time when UR was more accessible for undocumented students.

For Peter Kaufman of the Jepson School of Leadership Studies, the solution to this issue is as simple as “restoring the agreement” he said he had with the administration in 2009.

“There are many schools who just won’t take them,” he said, acknowledging that not all schools have adopted such progressive policies on undocumented and DACA students. “The real sad part here is that this is a school that was open to them and closed the doors.”

Kaufman, whose passion for social justice dates back to his involvement in the U.S. civil rights movement, started the Scholars Latino Initiative at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2003. SLI, which Kaufman called “the underground railroad to higher education,” had been extremely successful at UNC. Kaufman came to UR in 2008 at the institution's request to replicate the program here.

SLI is a college-prep program in which Latino high school students take a college-level class and are paired with a student mentor from a local university. SLI also includes an intensive summer program, an SAT course, community service projects and a cultural exchange component, all with the purpose of “incentivizing higher education” for students, some of whom have never stepped foot on a college campus, Kaufman said.

“I came here because the then-president was really excited to have the program here,” he said. “The 2008 agreement said that anyone who is eligible would be accepted and would receive full financial aid. That’s why I came. There was no other reason for me to leave what was a wonderful existence.”

This agreement is outlined in a series of emails, obtained by The Collegian, between Kaufman and the administration from 2008-2009 that show the university’s openness to accepting undocumented students regardless of their finances.

A January 2008 email from then-provost Joe Kent to Kaufman read: “Let me be clear that we will fully honor our commitment to meet the financial need of undocumented Hispanic students as well as the financial need of documented students in your program who are admitted to UR. The fact that we have limited funds for international students is true but not critical to this discussion. That is a matter for internal resolution.”

Regarding admission, in May 2008, Pam Spence, the dean of admission before Villanueva came to UR in 2009, wrote to Kaufman: “If your students are in the top 10-15% of their class, enrolled in a rigorous curriculum, and have SAT’s 500 ‘ish’ and above, we will certainly work with you.”

Nanci Tessier, then-vice president of enrollment management, wrote in a January 2009 email: “At this time, we do not plan to limit the number of VA SLI students (undocumented students and/or US citizens/permanent residents) ... Ed, Lori and I are excited about the wonderful work that you are doing to prepare students for higher education and to further link the University with the community in which we reside.”

Tessier declined to comment when contacted by email.

Kaufman still reminisces on the one “glorious year” in 2008 when his SLI students were able to compete in the domestic pool. They succeeded, he said, and 20 enrolled, 19 of whom graduated.

“And a year later they tried to get out of the whole thing,” he said.

In 2009, UR cut ties with SLI, and the program was abruptly shut down.

“They tried to cancel the program, we threatened legal action, we came up with a compromise, [those] 19 youngsters made it through,” Kaufman said.

Then-president Ed Ayers, who was mentioned in multiple email exchanges between Kaufman and members of the administration, declined to comment on the sudden change in the university’s stance.

For Villanueva, the problem is that UR has become considerably more competitive in recent years, with 12,000 applicants this year, he said.

“In this applicant pool, over 84 percent are competitive,” he said. “So we could admit — wow —9,000-plus for 800 [spots], and we only admitted about 3,500. So you kind of disappoint thousands of people that can be awesome here at this school.”

Because there is such a limited financial-aid budget for international students, that makes this pool even more competitive, he said.

“We’re not going to admit you here and not give you financial aid,” Villanueva said, adding that UR does not practice an “admit-deny” policy.

Still, the university prides itself in meeting 100 percent of demonstrated financial need for all admitted students, which it does through a sizeable overall financial-aid budget, he said.

“The budget here is incredible, it’s immense, it’s $72 million for less than 3,000 students,” Villanueva said.

But, he emphasized that standards to be admitted at UR are becoming increasingly higher and extend beyond grades.

“I can tell you we have valedictorians on our waitlist,” he said. “So it’s just not enough, I hate to say it.”

The space to self-identify as a DACA student was added on the Common Application two years ago, Villanueva said.

“Last year we had 38 students who told us that they’re undocumented,” Villanueva said. “We offered admission to two and enrolled one.”

The office of admissions provided verification that the enrolled DACA student still attends the university.

This year, 42 DACA students applied, and UR again admitted two, Villanueva said, adding, “We hope to enroll both.”

Looking to the future, Barbosa hopes to see policy change that will result in an increase in DACA students at UR, she said.

“This school may not be in a position to accept undocumented but at least accept DACA students,” she said. “I just want some kind of step forward, like put them in the domestic pool.”

First-year Kimberly Estrada and sophomore Kidest Gibre said they shared a similar hope. The pair chose to focus on “the educational disparity that exists for undocumented youth” for a WILL* Colloquium class project that tasked them with researching and advocating for change within an issue area, Gibre said.

Institutions comparable to UR recently adopted policies to increase accessibility for undocumented students, a shift that Gibre called a reaction to the new U.S. president.

“It was a reaction to all of the xenophobic policies that have been implemented since the new presidency,” she said. “We were hoping that the school would also react in a way that stands in support of undocumented students. ... Completely change the policy so that undocumented students are part of the domestic pool because they do reside in the U.S. and not just that but also be subjected to a need-blind admissions process.”

Kaufman likewise wants his SLI students, whom he affectionately calls his “youngsters,” to be able to compete as domestic students, as in the original agreement he had with UR, he said.

“We’re looking for a level playing field,” he said. “We’re not asking to get something that you have, we’re asking to compete for what you have.”

For now, Emma will take a gap year to work and figure out how to afford college. Laura said she would likely do the same, despite receiving admittance from her top three schools. Still, both remain hopeful and optimistic that their dreams to become the first members of their families to attend college will come true.

“Everything is possible,” Emma said. “It’s better to be optimistic, like my mom always tells me, ‘You’re going to reach your dreams someday, you’re still young, you have a lot going on.’ She was like, ‘At your age, I would’ve loved to be in your footsteps.'”

Laura, who came to the U.S. at the age of four, read aloud a passage from her sixth-grade diary to The Collegian. She wrote this diary inside a one-bedroom apartment she shared with her parents and brother in Florida.

She read aloud: “Life of being the first-born daughter of immigrants in a different country is hard. I feel like I never truly had a childhood. All my childhood was just me translating for my parents, filling out papers and worrying ... this is why ... I’ve got to push myself to do everything I have to do in college and be successful, not for me but to make my parents’ sacrifice worthwhile, and so that my children have the life I didn’t.”

For Barbosa, the hope of admissions policy reform stems from her deep appreciation for her school and her desire to make it a better place.

“Obviously I love UR because it’s given me so much,” she said. “But it’s because we love the school that we want it to change.”

Contact writer Sara Minnich at sara.minnich@richmond.edu.

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now