Junior Alexis Achey lives in the University Forest Apartments with her service dog, Winston, who helps her to manage her Type 1 Diabetes through his sense of smell, which detects when her blood sugar levels are out of range.

"He can smell the changes in body chem- istry as the glucose levels fluctuate," Achey said. "So when levels are high, it smells really fruity or sweet, and when low, it smells like nail polish remover or acetone."

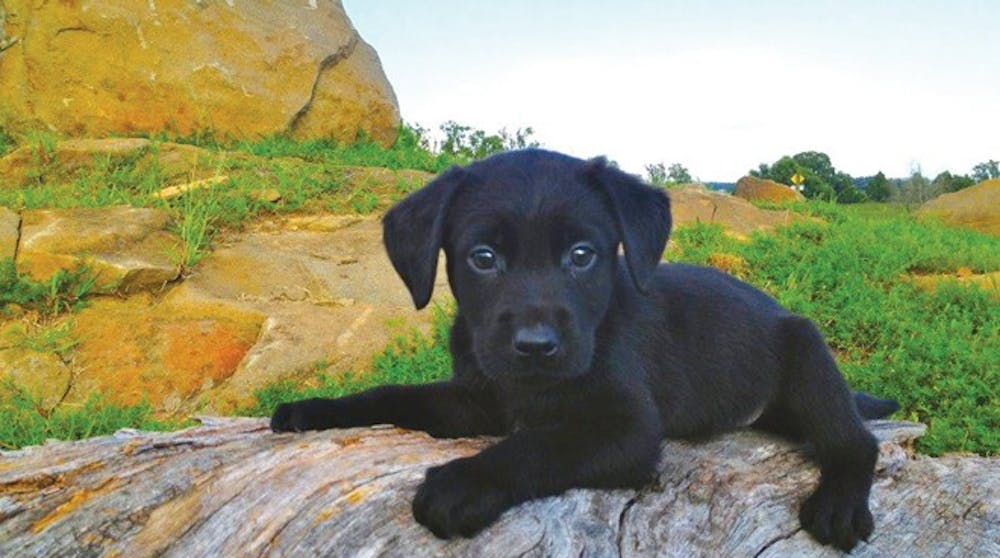

Winston, a three-month-old black lab, has not yet learned the paw-to-leg motion, Achey said, which is the official notification that fully trained service animals use to notify their owners that their sugar levels are off balance.

"Right now, he basically does anything he can to get my attention," she said, "be it whining, jumping or barking." He also gets the hiccups when her levels are out of range, Achey said, although she is unsure why.

Before living with Winston, Achey had to monitor her sugar levels on her own, she said. Doctors diagnosed Achey's Type 1 Diabetes when she was 7 years old.

Since then, she has learned to look out for symptoms of low blood sugar. "Nor- mally, you get blurry vision, shakiness, sweatiness, general disorientation," she said. "You would normally just feel off," she said.

When experiencing these symptoms, Achey would test her glucose levels to con- firm that they were lower than normal, and if they were, she would eat or drink something sugary. If levels remained low, Achey would have to rely on glucagon, she said, a drug that injects pure glucose into the body, usually in the thigh.

But within the last year and a half, she had become unsure when to take these pre- cautions because she had trouble recognizing the symptoms. "Since I've been diabetic for so long, my blood sugars have always been on the lower range," she said, "so as time goes on, I've lost the ability to detect it."

Failure to recognize these symptoms could result in a seizure, coma or even death, she said. Now, Winston can detect out of range levels about a half an hour earlier than the glucose monitors that Achey had used in the past could.

Because service dogs for diabetes have become popular within the past two to three years, Achey said that she had never heard of them until recently. Achey's research professor, Carol Parish, who raises dogs for Guiding Eyes for the Blind, told her about the option.

Achey started researching, she said, and found Service Dogs by Warren Retrievers Inc., a company based in Orange, Va.

Achey contacted the company at the be- ginning of February, she said, and was put on the wait list until she was matched with Winston in August and received him in September. But before Achey could live with Winston, he had to go through a training program.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

"So the company had him in 'puppy boot camp' since he was five weeks old until 12 weeks old," she said, "and they just learn basic obedience and alert, but don't necessarily learn the smell." At five weeks, the dogs are evaluated to see whether they are curious about different smells. Finally, the dogs go through temperament testing, which helps to match them with their owners, she said.

The company bases these matches off of personality and lifestyle, Achey said, which is determined for the dog through training, and for the owner, through forms similar to roommate applications.

Once matched with Achey, Winston's training did not end, she said. When Achey first got Winston, she worked with a company employee to train him eight hours a day, five days a week. An employee will continue to help every three months until Winston is two years old, she said.

Service Dogs by Warren Retrievers helps its clients to pay for the purchase of the dogs and their training, according to the company's website. These costs add up to $20,000, Achey said. To raise this money, Achey has posted her fundraiser on Facebook, selling shot glasses and beer glasses that read, "In dog beers, I've only had one."

Before she could bring Winston to campus, Achey had to contact the housing office because of university regulations prohibiting animals from living on campus. After applying for housing, she was assigned to a room in North Court, Achey said, until mid-summer when she was notified that a reserved handicapped apartment was available.

Achey is the first student to live with a service animal on the University of Richmond campus, she said. "There was a request several years ago from a potential first year student," Joan Lachowski, director of undergraduate housing, said. "It would have been approved if he chose to come to the university."

The university has a policy permitting students with disabilities to live with a service dog in on-campus housing, Lachowski said. But in the future, all specific requests for service animals would have to be approved based on university policy and guidelines provided by the Americans with Disabilities Act, she said.

Since Achey has been granted this permission, she said that her daily routine at school has changed. "I have to leave, on average, a half an hour earlier for class than I normally would have," she said, "to let him go to the bathroom if he needs to and because so many people stop him along the way."

Attention from multiple people can create a problem for Winston. "Winston is on duty 24/7, so work and play are a lot more integrative," Achey said. "While he's playing, he still has to pay attention to me. As long as I tell him to sit down, people can pet him, but it's ideal to have only one person at a time."

Winston stays with Achey in the classroom, as well. Some of Achey's, physics and chemistry teachers voiced concern about having Winston in the wet labs, Achey said. To avoid any problems, Winston wears safety booties, and once he is older, he will wear goggles, or "doggles," as Achey called them.

Although unsure whether she wants to have a service dog for the rest of her life, Achey said that Winston's services had definitely been an improvement from the glucose monitors that she had relied on in the past.

Contact reporter Jamie Edelen at jamie.edelen@richmond.edu

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now