Timothy Patterson is not a student in my class. I've never met him; I wouldn't know him if he was sitting next to me at a Spider football game. He never spoke to me personally about Robert Crumb or his work, even though, as students who are in my class can confirm, I've been in my office often during the last several weeks and have been very much available to talk about Crumb, and what my class is about (accurate title: American Misfit: Geek Literature and Culture), and why I feel it is important for professors at institutions of higher learning -- including the University of Richmond -- to include Crumb on their syllabus if they so desire. I would have been willing, even eager, to have that conversation with Patterson, but he apparently felt strongly enough to write publicly about the "values this university claims to hold dear," but not strongly enough to meet privately with the professor who assigned the material.

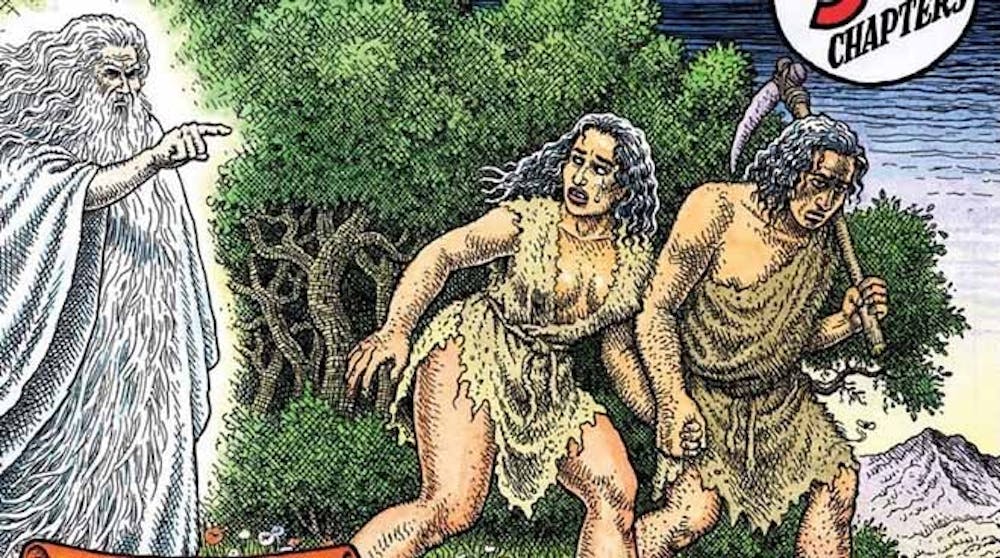

Because he chose not to meet with me I will tell him publicly what I would have told him privately: I apologize for nothing. I plan to teach my Geek Lit course again, and when I do I will absolutely again assign Robert Crumb's "My Troubles with Women." We will also watch "Crumb," a documentary on him and his brothers, again. All told, including "My Troubles with Women," "Crumb" and debriefing Robert Crumb's Modlin-Center-sponsored appearance at CenterStage downtown, we spent more than four hours of class time discussing Robert Crumb and/or his work. It was well worth it.

Patterson should understand that although it's true that professors can assign anything they want, these professors must also lead meaningful discussions about that material. If he had been in my classroom, he would have had to support his contention that Crumb's work "delves into the realm of the subversive merely for the sake of being subversive." I have no idea how he or anyone could know that for sure about Crumb's work. Crumb, himself, is only so helpful in understanding his work.

On the day we discussed the documentary "Crumb," one student was left when I finished packing my bag after class, and it happened to be one of the female students -- and she was by no means the only one -- who was offended by Crumb and his work, and said so during class. "I appreciated your candor," I said to her just as she reached the door, and the surprised expression on her face led me to believe that she was thinking: "What? That? Of course -- what else would I do?" Her reaction suggested that she was surprised that anyone would thank her for being candid. But I did thank her. Because I value candor. The fact that I don't have any idea who complained to Patterson about "My Troubles with Women" suggests that whoever it is, he or she doesn't value candor and expressing feelings up-front as much as I and my candid female student do, because that person would have come to me and expressed whatever misgivings he or she had with Crumb and his work, even if he or she felt the need to publicly air those views after our meeting. Instead, I found out from Suzanne Jones, my department chair, who found out from Dean Boehman, who, apparently, found out from Timothy Patterson, who must have found out from our disgruntled mystery student. One of the things I value is the ability for someone who feels aggrieved to meet with the person with whom they have a grievance and clearly state their problem, opening a discussion on the topic. It would have been a conversation that I would dearly have loved to have. It's my job to have that conversation.

If Patterson had come to talk to me I would have shared with him that I, too, was offended by aspects of Crumb's work. I would have showed him where and how Crumb grapples with feminist critiques of his work right there inside his work. I would have demonstrated for him how well the text fits into our semester-long discussion of geeks and nerds. I also would have shared with him the fact that I routinely assign edgy and provocative texts that have the potential to offend students. For more evidence, just ask students in both sections of the 20th Century American Fiction class I'm teaching this semester. Or ask students in my Blackface seminar last spring (a course I'll be teaching again next spring). "Edgy and provocative is what I do, Mr. Patterson," I would have said, and yes, academic freedom protects me. I taught for eight years at a religious institution, the College of the Holy Cross, before the five-plus years I've spent here at the University of Richmond, and even though I was assigning and teaching difficult, potentially offensive texts both there and here, this is the first time anyone has needed to reach out to an advocate in order to address any of my selected texts. I hope the next time it happens--and it likely will--that the offended student can represent him- or herself, so that I won't have to discover someone's been offended third- and fourth-hand.

Although it's true that I was offended by some of Crumb's work, I didn't let that stop me from putting his book on the syllabus. I'm offended by Miles Davis' abusive treatment of women, but I haven't let that stop me from putting him on my syllabus. I'm offended by Pablo Picasso's abusive treatment of women, but haven't let that stop me from putting him on my syllabus. I'm offended by a middle-aged man having sex with a thirteen-year-old girl, but I wouldn't let that stop me from putting Nabokov's "Lolita" on my syllabus. I'm offended by a man having sex with his young daughter, but that hasn't stopped me from putting Ralph Ellison's "Invisible Man" -- or "Sapphire's Push" -- on my syllabus. Such gestures raise the question of what's appropriate for art; indeed, it questions just what makes a song, or a painting or a novel, art -- and we discussed those exact questions during our in-class examination of the life and work of Robert Crumb.

I don't take lightly the matters Mr. Patterson has raised. He asks, "[W]hat are the bounds of academic freedom? Is it really permissible for any professor to include anything he or she desires in any class?" Questions like these go to the core of why I'm here, and why I execute the classroom and scholarly work I do here. He can employ words such as "the values this university claims to hold dear," but every time I enter the classroom I'm attempting to live them. For me, the values of this university include intellectual inquiry of the highest order of a variety of challenging and difficult texts, texts that may well force us -- myself and my students -- out of our comfort zone. I'm confident that we executed just that during the four-plus hours we discussed Robert Crumb and his work. I'm proud of my students for the way they expressed themselves in class, the way they grappled openly and honestly and, yes, candidly, with Crumb's difficult, exceedingly valuable work, and I'm absolutely and enthusiastically including the women who exercised their academic freedom -- right there in class, out loud, during the discussion -- to question and interrogate, and, yes, openly condemn Crumb's work. My conception of the values this university holds is that both of the following need to constantly be in play: I absolutely do, have and will continue to exercise my academic freedom to assign the texts I feel are necessary for a full treatment of the class subject, and yet when provocative texts do their work and do, indeed, provoke, I will continue to give space for whatever varied reactions that might arise. I do that as a matter of course. I wish Patterson could have been there to see it.

But he's never visited my classroom, nor has he ever visited me. So let me make clear to him and anyone else who, like me, feels strongly about issues of academic freedom: I love sitting on panels and talking in public about such matters, and would be more than willing to sit on just such a panel if invited to do so, now or in the future. I have no doubt that the resulting discussion would credibly demonstrate the values that the University of Richmond holds dear.

Sincerely,

Dr. Bertram D. Ashe

Associate Professor

English and American Studies

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Support independent student media

You can make a tax-deductible donation by clicking the button below, which takes you to our secure PayPal account. The page is set up to receive contributions in whatever amount you designate. We look forward to using the money we raise to further our mission of providing honest and accurate information to students, faculty, staff, alumni and others in the general public.

Donate Now